-

Look to 1950s sci-fi to appreciate the genius of Gene Roddenberry

Perhaps the best science-fiction radio series ever produced was X Minus One. NBC broadcast 126 episodes from 1955 to 1958, with stories from preeminent writers of the period including Ray Bradbury, Robert Silverberg, Philip K. Dick, Robert A. Heinlein, Robert Bloch, Frederik Pohl and Fritz Leiber.

And Clifford D. Simak. Simak’s novels and short stories landed him a Nebula Award and three Hugo Awards, plus two Retrospective Hugo Awards.

The Big Front Yard won a Hugo in 1959 Six of his stories were adapted for X Minus One, including Courtesy. That radio play told “the story of the second expedition to the planet of Landro” in which 180 men attempted to colonize a “god-forsaken sphere” already inhabited by an indigenous population.

In Simak’s tale, the planet’s “aborigines” are described as “strange, ugly little people” and “cave rats” and, when it is suggested they may hold an important answer to a peril faced by the humans, one crewmember promises the commander he will “get a few of them and beat it out of them.” And it gets worse from there.

Gene Roddenberry was a fan of early pulp sci-fi, and the stories written in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s taught him about the genre but, when he committed his view of the future to paper in the 1964 Star Trek is… pitch and wrote The Cage pilot episode, his heroes would act very differently from Simak’s. Roddenberry wanted humans to explore strange new worlds and seek out new civilizations, not beat members of those civilizations to death.

Click the YouTube link below to listen to Courtesy, recorded in 1955, and contrast it to the spirit of The Cage, filmed only nine years later.

Simak’s story offers up a weak, mystical note of redemption at the end that does little to erase the ugliness of what came before. But I called X Minus One the greatest of the sci-fi radio series because the show often delivered great tales.

Cold Equations, broadcast just after Courtesy, is one of those. The hard sci-fi story absolutely sticks the landing, and adventures like these also inspired Roddenberry.

-

Not a modeller? Pay a pro. You’ll love the result

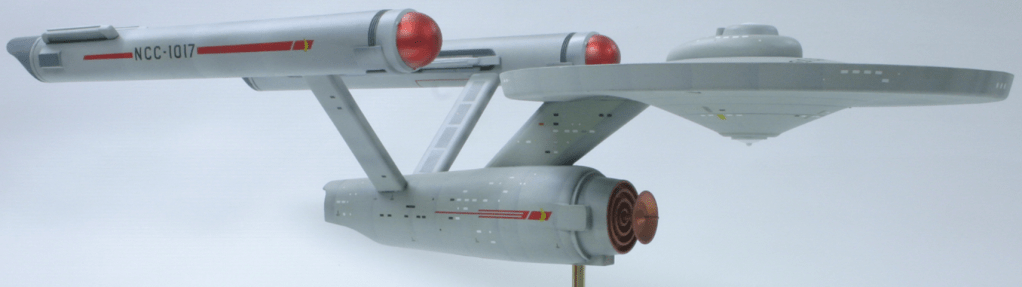

I recently commissioned a build of the AMT Enterprise kit from an experienced modeler — and I am thrilled with my new acquisition. It’s vintage and cool and executed with a lot of skill. It’s exactly what I wanted.

And it’s been a long time coming. Like most fans of around my age, I tried to build an AMT kit back in the day, but in addition to the poorly joined pieces and the glue everywhere, I had no idea how to paint the thing. I gave up.

Decades later, I found James Small at Small Art Works in Nova Scotia. He is an experienced professional who has also worked on movie models (for Battlefield Earth) and has been the go-to builder for Round 2, the company that manufactures models under the AMT and Polar Lights brands, among others. He’s constructed more than 100 kits for the company, including all the Star Trek, Star Wars, and Space: 1999 models since about 2009. His builds are used for the vendor’s product shots and his name is on the boxes. So, you know he’s good.

The age of assessment

This commission came about now because I am in what I call the assessment phase of my hobby. Collectors spend years acquiring, because there’s a lot of cool stuff we don’t yet own. Eventually, though, we step back, appreciate what we already possess, and begin to contemplate the gaps, the rare or expensive items that are not yet on our shelves.

An AMT Enterprise was one such gap, although the kit itself is neither rare nor expensive; the recent reissue of it can be yours for about C$60. What is rare, for me, is the skill required to create a really nice build.

If you don’t know the difference between Revell Contacta Clear and Tamiya Liquid Cement — and I do not — hire a pro like Jim. The results are great.

Which kit, and how accurate?

I had to decide which AMT Enterprise to build, and to understand that question we need a little history.

AMT made 10 different versions of the Enterprise over the decades since 1966, and that does not include special editions like the cutaway ship. Memory Alpha has a good summary chart of these products.

My goal was to finally own the model I couldn’t have as a kid, so I wanted a really old kit, right? No. They’re quite expensive but the real problem is that the nacelles eventually droop, as the point where the pylons connect to the secondary hull was too weak in the original kits.

The other issue is that older kits are less accurate, but that didn’t bother me. I own the Polar Lights 32-inch model so I have a ship that’s true to the TV show. My goal here was nostalgia.

That goal also ruled out the newest reissue from Round 2. The newer versions are closer to the real model, but that means they are less old-timey.

The option I chose was already on my shelf: an AMT kit dated 1983 on the box, although I think it was originally released in 1975. It wouldn’t suffer nacelle droop and was from around the time I tried to build one myself.

I mailed my kit off to Jim, and then the questions started, because there are a lot of ways to build these kits. For example, AMT added raised grid lines to the saucer on many of its versions, including mine. Some modellers painstakingly sanded these down. What did I want Jim to do? I opted to keep the lines, as teenage me would have done.

Did I want it painted white or light grey? Light grey. Did I want the front of the nacelles painted red, dark red, copper, or gold? Red with gold highlights. What about the flimsy stand that came with the model? Give me the flimsy stand for when I am feeling authentic but also make me a new one so my ship won’t fall over. (You see both in the photos below.)

And then there were the windows, a significant decision:

Do you prefer the window arrangement/decoration as shown on this model done “old school” (and as etched into the plastic) as the kit was originally?

Or a more “authentic” look, like this?

I agonized over this call, but I went with the old-school look, again to honour the idea that this was a model I might have built as a teen.

I love my AMT Enterprise, and I very much appreciate that Jim asked me all those questions and that there are still people out there with the knowledge and skill to build these things well. Pay a pro to build a model, if you can. The result will be gorgeous and you’ll be supporting a hobby and skillset that are, sadly, disappearing.

Here are photos of the model Jim built for me.

Jim and I also discussed the state of modelling today, and it’s an interesting — if melancholy — read.

-

The state of modelling, then and now

Modeling has changed dramatically over the last few decades. Once every young sci-fan, and indeed every horror, airplane or car aficionado, glued and painted plastic model kits, or tried to. Today, far fewer people assemble these shaped sheets of plastic into fantastic spaceships or cool hotrods.

James Small Professional modeler James Small, who recently built my AMT Enterprise model, supplied this grim assessment: “Unfortunately, it’s a dying hobby. Enjoy it while you can.”

Modelling was once big business

AMT launched its Enterprise model kit in 1966, and it was a huge success as soon as it hit store shelves. Star Trek Associate Producer Bob Justman told Gene Roddenberry in a memo dated October 19, 1967, that:

I have it on reliable information that the “STAR TREK” Model Kit will sell more than a million copies within its first year of production… All I know is that the machine which turns out the plastic parts for the kit goes continually 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and AMT is rushing another machine into production, so that they can keep up with the demand.

(I wrote about the Enterprise and other AMT models in an article that mostly covers how much it cost to build the Galileo shuttlecraft.)

Sadly, Jim told me the heyday of modelling is well in the past.

When I was a kid, almost everyone made model kits at some point, and that simply doesn’t exist anymore. The audience for model kits today is pretty much adults my age, which is why they cost so much now. We used to buy model kits at the five-and-dime store; a Matchbox airplane kit was $1.25 and now those types of kits are $50.

Jim got into modeling through airplanes.

It started with airplanes. I think the first one was a Matchbox kit of a Boeing P-12E. I did a horrible job, it was a difficult kit for a kid to build, but it was still interesting.

Photo from scalemates But it was Space: 1999, a show I’ve never liked although the ships are cool, that really cemented his interest and later led to work with Round 2, the preeminent model manufacturer today.

I loved Space: 1999 and…I first learned about making models for movies and TV from reading the book The Making of Space: 1999. I opened it to photos of Brian Johnson and Nick Alder holding that 44-inch Eagle model and it was sort of like a kid discovering a magician’s trick. Then Star Wars came along and I gobbled that up, and it just continued from there.

Nick Alder and Brian Johnson. Photo from The Prop Gallery I had the old MPC Eagle kit from around 1975 but I was never satisfied with it, because it was not terribly accurate. It didn’t match what I saw on screen; it was simplified and the proportions were off, and I always wanted a better model. Then Round 2 hired me in 2008 or so to do some build-ups for them, and I’ve been working with them ever since. Around 2013, I became friends with Jamie Hood, one of the product developers there…and I kept bugging him to do the Eagle from Space: 1999. Then they got the license and they released the old kit and it started flying off the shelves. He couldn’t believe it. They released the other kits too, like the Moonbase Alpha, and I said you have to do a much better model of the Eagle.

I knew a guy named Chris Trice who had access to the original 44-inch Eagle miniatures and he had measured them and built replicas that were superbly accurate, and a guy named Daniel Prud’homme had done some blueprints of the Eagle based on Chris’ measurements. So I said to Jamie “Here’s how you get the Eagle done. All of the design work is already done.”

He took my advice and they built it and it is one of the best-selling kits they ever had.

But even with sales successes like that, modeling is not what it used to be.

The technology has advanced to the point that kits are much better and in fact cheaper to produce and at better quality, but because they’re not selling in the numbers they used to — they used to sell in the hundreds of thousands and even millions, and now they’re selling in the low thousands — the cost per unit is way up.

Kits got better, but fewer people are buying them now.

It’s sad to think that models and the skills of modellers may disappear soon. If you can, buy a kit and build a model, or hire a pro like Jim to do it for you. Either way, the ship you put on your shelf will bring you joy.

-

Colour guides are great comics collectibles

One of the best things about being a Star Trek collector is the community of experts and other collectors who are happy to share their knowledge. A good example is a recent assist from comics expert Mark Martinez about colour guides.

(Mark is online at X, Bluesky, and his extensive site, and he is active in the Star Trek Comics Weekly Facebook group.)

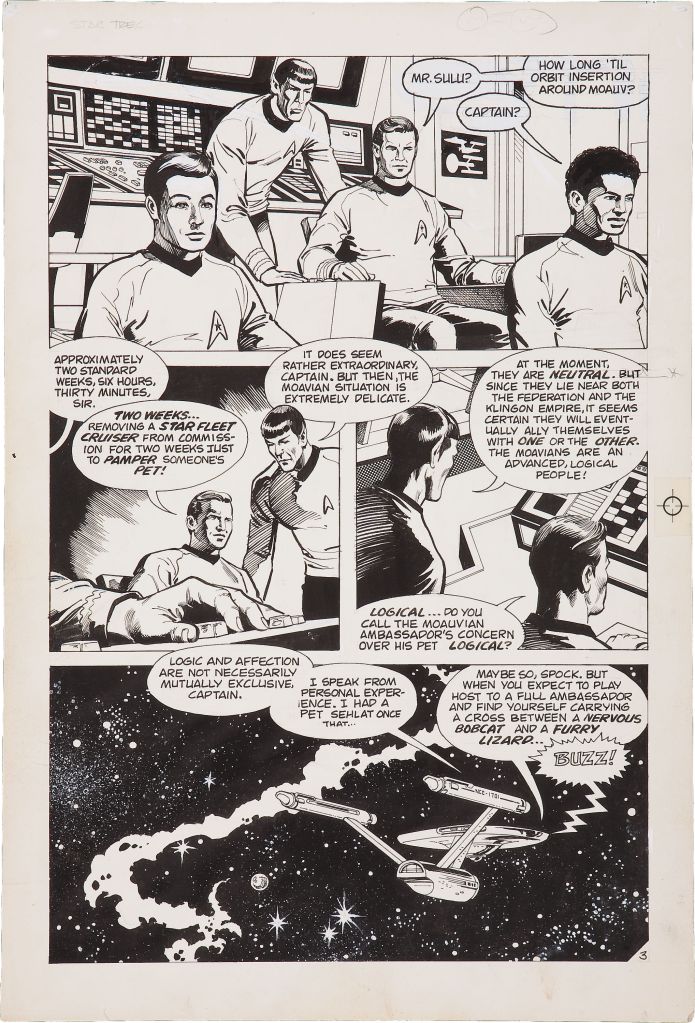

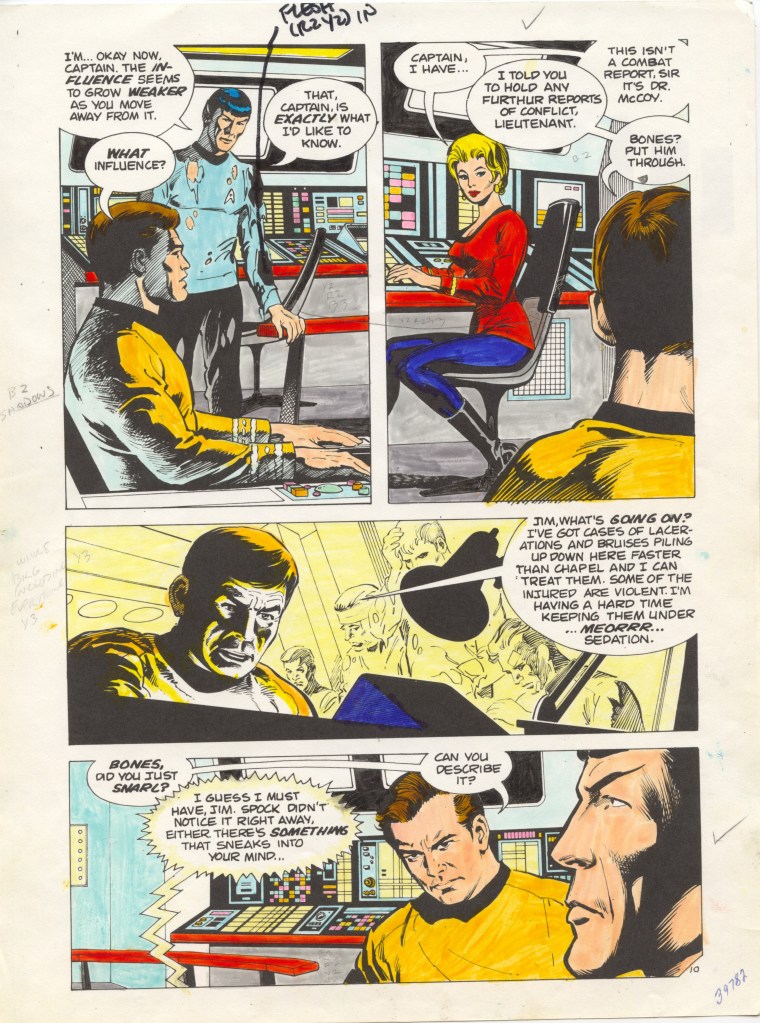

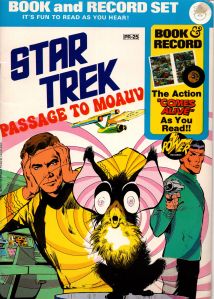

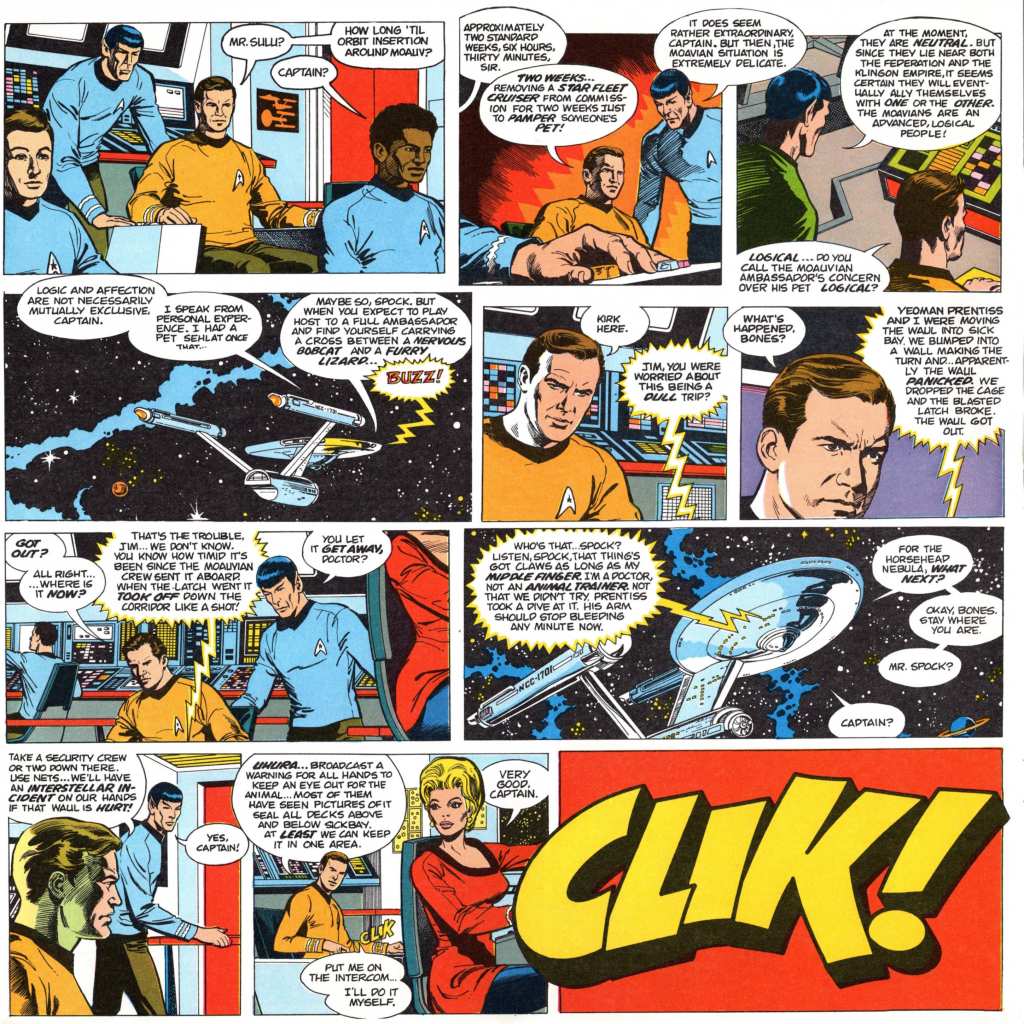

I first heard of colour guides on that Facebook group. Being familiar with these meant I knew what I was looking at when some popped up on eBay, and I bought one immediately. My page is from the Peter Pan comic-and-record set for the story Passage to Moauv. I wrote about that tale here.

Creating comics: a quick overview

Some comics are produced by one or two creators who do all the work themselves, but larger companies employ a team, each fulfilling a specific purpose. Scary Sarah has written a good overview of this process; here are the main players.

- The writer crafts a script.

- A penciller creates the basic images.

- A letterer renders the text in a readable format.

- An inker makes the drawings into black-and-white line art.

- A copy of the art is used by a colourist to specify the hues for each element.

- The resulting colour guides are passed to a colour separator to prepare negatives for printing.

Computers are now employed during the colouring process, so traditional guides are rarely made.

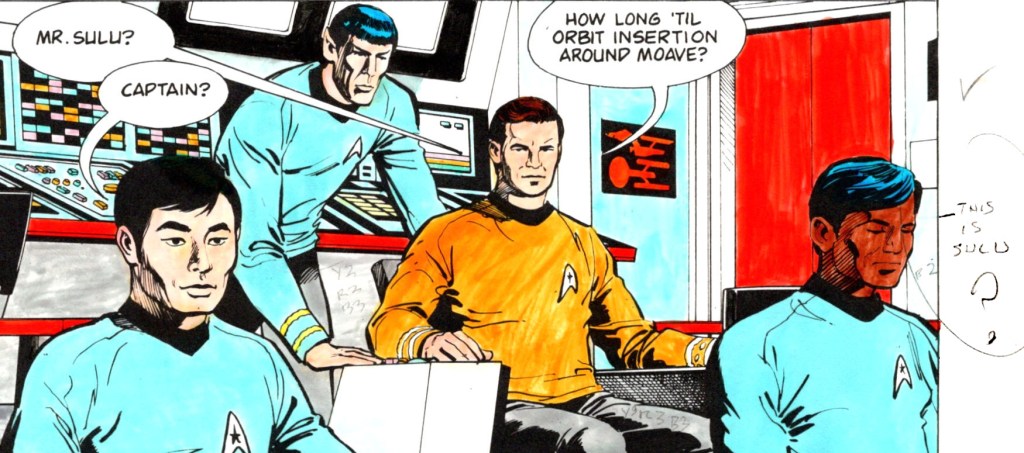

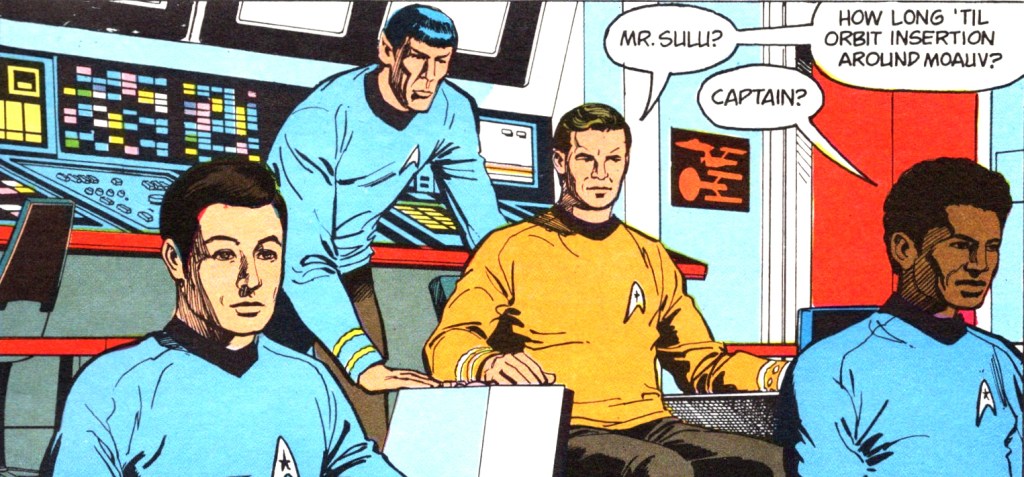

Unique pieces of artThe drawings used for guides are copies (often photocopies), but the colours are done by hand, using pencils, felt-tip pens, watercolors or any combination, according to Mark, so each colour guide is a one-of-a-kind piece of comic art.

These guides also give some insight into the creation and editing process. For example, my page includes the penciled question “This is Sulu?” And no, it isn’t; Sulu is on the left of the drawing, and the question indicates the black character sitting at the helm station.

So why the odd question, and why — in the actual published book — has the drawing been reworked? The final comic replaced the familiar figure of Sulu with a generic navigator and instead has the black character answer to “Mr. Sulu?”

One piece of background information answers both questions: Peter Pan had licensed only the likenesses of Kirk, Spock and McCoy. The artist either did not know about this rule or completed the drawing while the licensing was still being finalized. The legal arrangement meant Sulu as we knew him had to go, and this is also why Peter Pan usually depicted Uhura as a blond white woman and Arex as a big blond human.

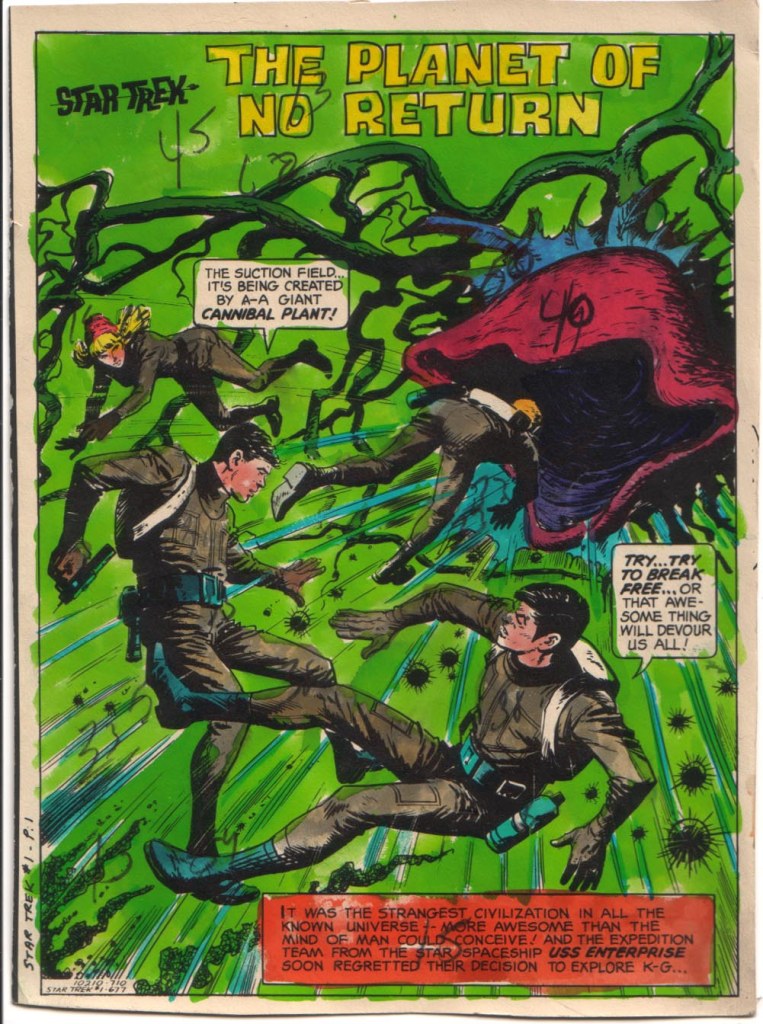

Mark sent me scans of the line art for my page, the colour guide for another page in the same story, and two guides from the first Gold Key comic, The Planet Of No Return. (Note the red cap on Rand in the Gold Key images. The artist or the coulourist thought the Yeoman’s elaborate beehive hair was a hat.) Thanks for sharing these, Mark, and for giving me permission to use them here.

Postscripts

The seller I purchased from still has a number of guides up for auction, at time of writing.

Many of the Peter Pan titles were repackaged with 33 RPM LPs, instead of the smaller 45 RPM discs. The larger format meant the layouts had to be redone. Here is the LP version of my page.

-

A collecting Q&A

A guy named Alex contacted me a year ago to ask if I would contribute to his new Star Trek site. His idea was to interview active fans, “especially those that go above and beyond like bloggers, YouTubers and others like you.” He would send me questions and post my answers on his site.

He had already engaged with John Champion of the Mission Log podcast and Trekland’s Larry Nemecek, so it was nice to be asked.

I emailed my answers but then his site disappeared from the Internet shortly after, and messages to him bounced back as undeliverable. I hope Alex is okay.

So I am posting those answers here, just so the effort was not entirely wasted. There is some solid advice about starting your own collection.

What inspired you to start collecting Star Trek memorabilia?

There are two facets to my collecting. The first is a love for Star Trek, particularly the original series, and it makes me happy to look around my Star Trek room and see a bunch of collectibles. The second is that I enjoy collecting itself. That means if Star Trek did not exist, I would likely collect something else. (Probably Humphrey Bogart memorabilia; I am on a quest to see and own all 74 of the movies he was in.) It’s good to have a hobby, and it’s a lot of fun to learn about a topic and then pursue items related to it.

So being a Star Trek collector is about both the show and collecting.

Having said that, I bought my first items at around 11 years old, so I never really decided to become a collector. I just bought a couple of things, then a couple more, and I realised I was enjoying it. And now I have thousands of items.

Can you recall the first piece of Star Trek memorabilia you acquired?

Yes, it was a used copy of The World of Star Trek, by David Gerrold — autographed by Gerrold. I purchased it in a great sci-fi bookstore in Toronto (Ontario, Canada) called Bakka. It still exists, although it has moved to a new location. I then bought a couple more Star Trek books at the same store, and that was it for me. I was a collector.

So it began with books, but then my collecting took a big jump forward when I attended my first science fiction convention. I discovered there are things called dealers rooms and they are packed with stuff to buy. Amazing!

How has your collection evolved over the years?

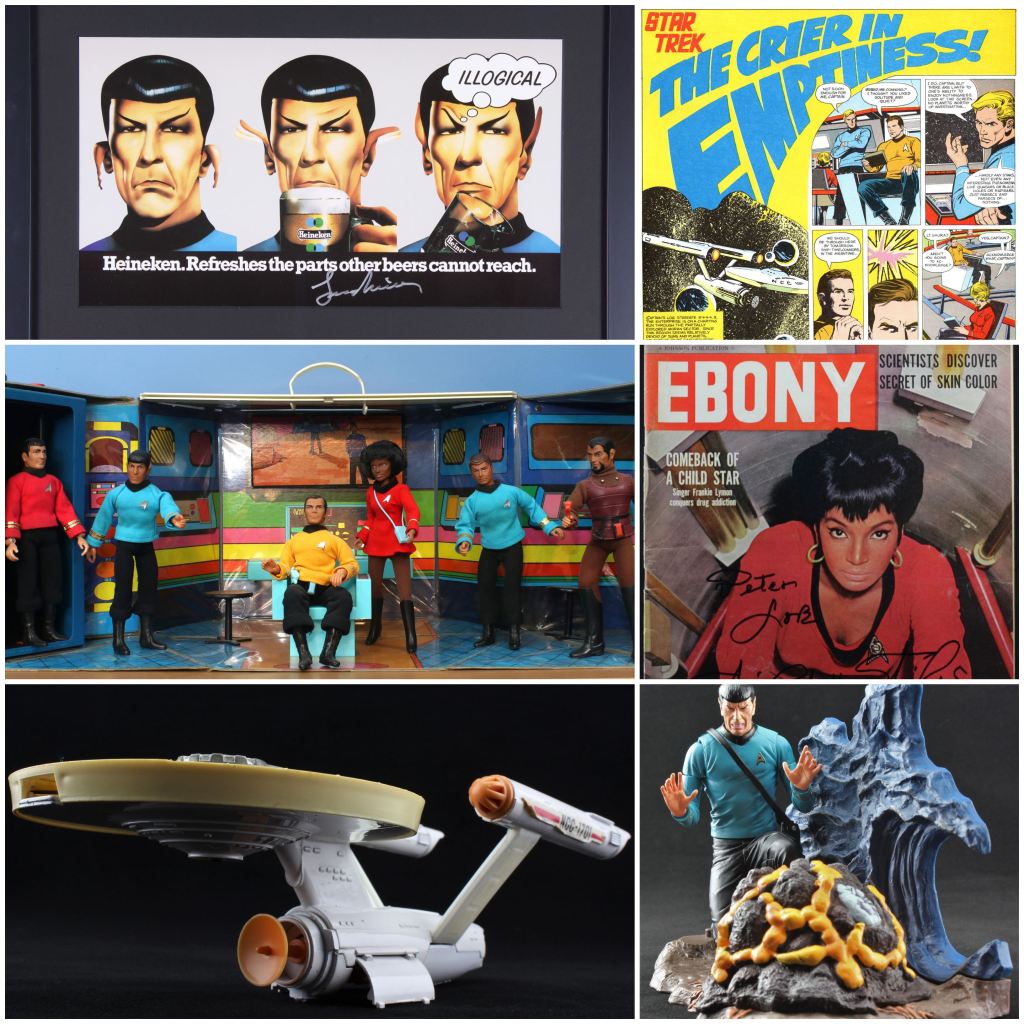

I have gone through phases, and I think most collectors do this. In the 1970s and 1980s, collectors bought pretty much anything that said “Star Trek” on it, because there was so little memorabilia. We had books and blueprints and the Mego toys and, if you went to a convention, a lot of 8×10 photos and some homemade items. That was me, starting in about 1979. I bought all of that.

I spent a lot of time getting autographs at conventions, mostly on 8x10s, and then I went through phases: books (non-fiction and novels), collectible plates, comics (notably the wonderful Gold Key line), cards, and then later the high-end models and figures that started to come out and also vintage toys.

The years 1964 to 1979 are now for me the most interesting era of Trek collectibles, for a few reasons. First, fans kept the show alive in the 1970s; if not for them, there would have been no new Star Trek after 1969. Second, that stuff is older, so it’s more fun to collect. And third, items from then are rare, especially the toys. These were made to be played with and they were, and then most often thrown out.

My current focus is on production-related information and material from 1964 to 1969. I own a number of memos and outlines, and I have gigabytes of scanned documents.

What’s the rarest or most challenging item you’ve ever obtained for your collection?

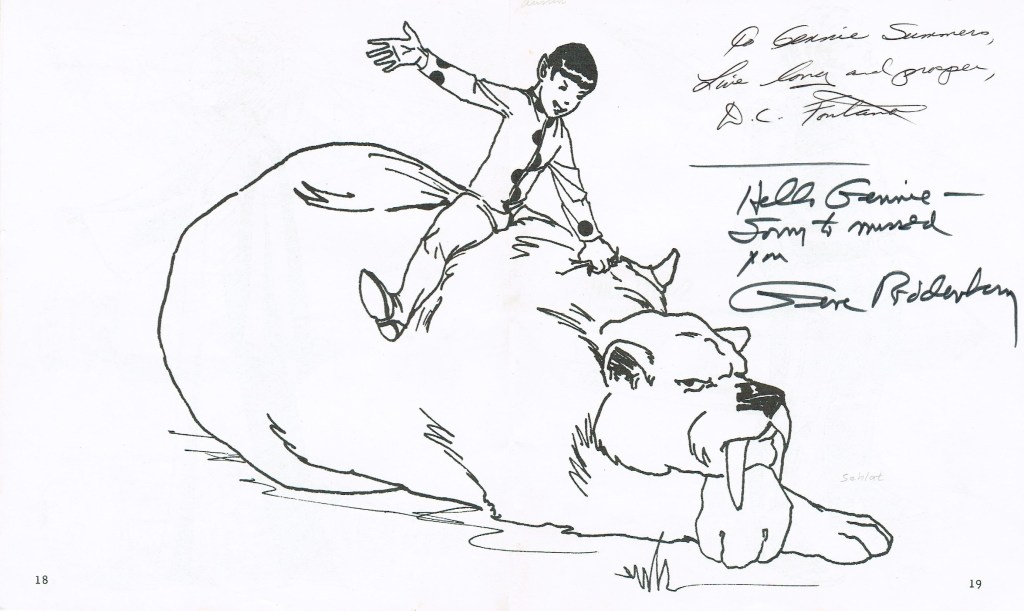

I have a few items that are literally one of a kind. The oddest one, and one of my favourites, is a piece of artwork drawn for the wrap party from the 1971 Gene Roddenberry movie Pretty Maids All In A Row. This was passed around at the party and signed by the cast and crew. I don’t know who did the drawing but it is signed by Gene Roddenberry, William Ware Theiss, Angie Dickinson, and Anita Doohan (James Doohan’s wife), plus many others.

The movie itself is terrible but it holds an important place in Star Trek history, and I will write a large article on the piece one day.

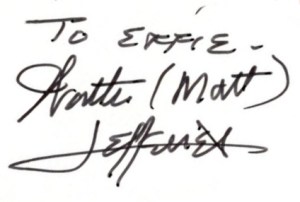

I also own the story outline for Amok Time, typed by Ted Sturgeon and given to Gene Roddenberry; a few other original typed story outlines and scripts; some personal (not convention) autographs by Matt Jefferies; and some letters and memos signed by Roddenberry. All of those are one of a kind.

Are there any specific gaps in your collection that you’re actively working to fill?

There are a couple of large gaps but I can’t say I am actively trying to fill them, because the items are rare and really expensive. I do not have the 1967 Leaf cards or the Mego Mission to Gamma VI playset (but I do have a vintage Enterprise playset in great shape). I would love to own anything related to Wah Chang’s Trek work and an original Jefferies set drawing. And every collector dreams of owning a screen-used prop, but those are incredibly expensive and there are a lot of fakes.

I have some small holes in the line-up, but I am enjoying filling those slowly, rather than just hitting eBay for everything. For example, I am missing a handful of the DC TOS comics and I decided it’s more fun to get those issues by flipping through boxes in stores and at conventions.

How has your passion for Star Trek influenced other areas of your life?

My passion for the show informs who I am today. The original series taught compassion, it said loyalty and friendship and honesty are important, and it advocated for science and scientists, for a rational approach to solving problems based on evidence and experience.

My passion for collecting also influences where I can live. If I move someday, my new home has to have a large Star Trek room. I have one now and the walls and shelves are full.

Do you have any favourite stories or anecdotes related to your experiences as a Star Trek collector?

Many, but I’ll mention only a few.

In my early teens I did not have a lot of money and so I didn’t get autographs, but then I started watching the autograph areas at conventions and I realised that what people are actually buying is a few minutes with someone who was there, on the set of this show we love, and the autograph they take home is a reminder of that experience. So I started paying for autographs at conventions, and I have a number of stories on my site about the conversations those few dollars got me. (Nichelle Nichols, Leonard Nimoy, George Takei, Howard Weinstein, William Shatner and William Shatner, and Shatner and Nimoy.)

And one time I found three amazing autographs I did not even know I had, when I opened an old colouring book. That story is here.

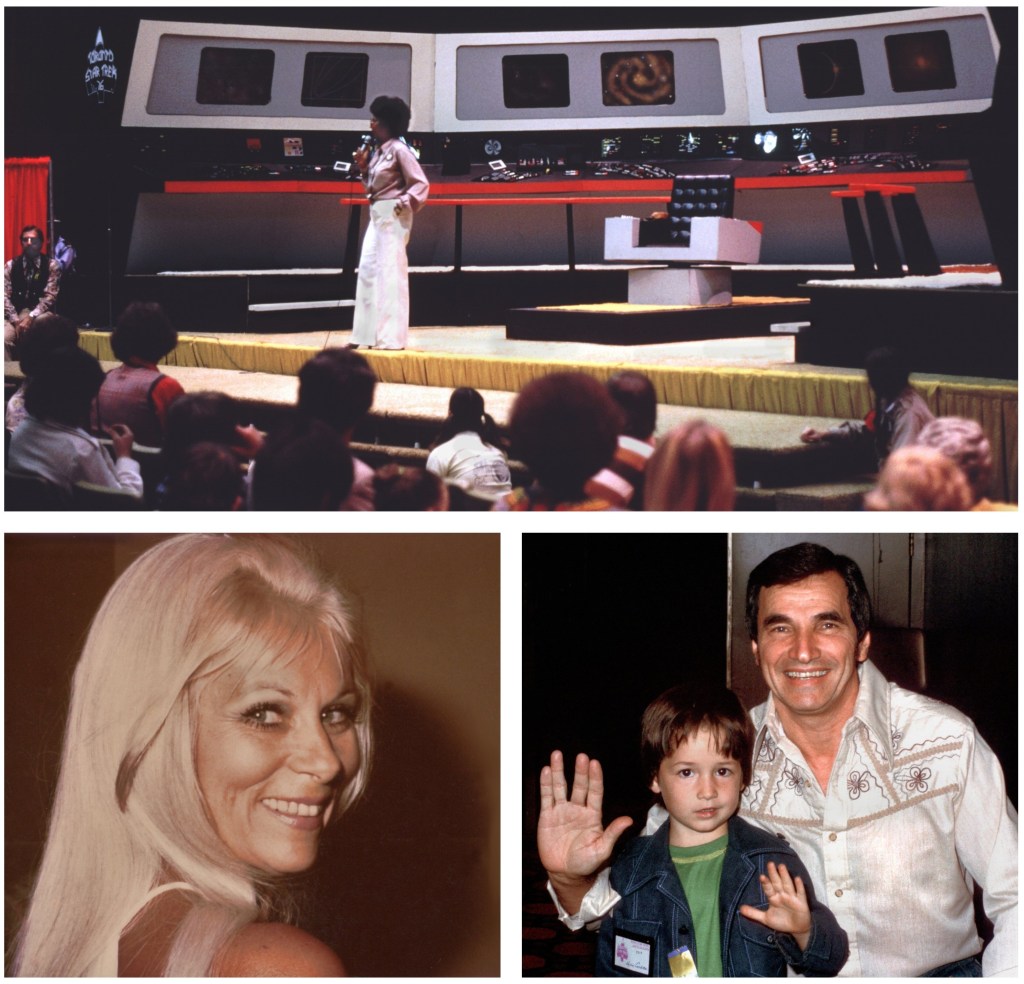

My favourite story, though, is about a convention pretty much everyone had forgotten. I was digging through a storage box and I found the program for Toronto Star Trek ’76; I had bought it years earlier because it was signed by Walter Koenig. I found out nothing was written about the con, and so spent three years interviewing people and writing the definitive history of the show. That story lives on its own site now.

Can you share any tips or strategies for effectively managing and growing a Star Trek memorabilia collection?

If you have not yet chosen what to collect, go with something small. Stamps bore me but collecting them would be very convenient, as you really just need a few binders on a shelf.

But if you’ve chosen Star Trek, collectors should begin with autographs, because they’re a lot of fun. Get all your first signatures on 8x10s. The photos are cheap, they’re easy to display, and the signatures themselves show up well. I have seen people get models signed, for example, and curved plastic surfaces are tough to sign and the autographs often look crummy.

Also, I recommend you set some limits on what you collect. I decided early on to only collect original series. I have seen every minute of every Star Trek show and movie and a lot of it I like, but I only collect TOS. That has been a good decision. Some people only collect models or comics or books. Whatever it is, setting some limits is often a good idea.

Once you have a sizable collection, go through it once in a while. Pull books off shelves, open storage boxes, go through your piles of magazines… You then enjoy the stuff you already have and will probably find things you forgot you purchased. That has happened to me many times.

Are there any items you’ve been searching for but haven’t been able to find?

Here’s an odd one, but a real example: I tried for many months to get in touch with author and collector Allan Asherman. He had been very active in the 1970s and 1980s but had stepped back from public life. I really wanted to talk to him about early fandom and his collection. I emailed, sent actual letters, and talked to a number of people who knew him and tried to communicate my interest. And then he died in September of 2023. If he received any of those inquiries he chose not to speak with me, and of course had every right to make that decision, but I do hope he at least heard I was interested. If he then decided against it, that’s fine. I wish I could have talked to him about early fandom.

Another is a research initiative that has gone nowhere. John D.F. Black wrote an envelope story for The Cage called From the First Day to the Last. Of course, Roddenberry’s The Menagerie script was made instead. Part two of Black’s script exists but I and other Star Trek historians have not seen part one. It is not even in the library of papers at UCLA. I have asked everyone I can find. I would love to read that.

What is your favourite Star Trek series and character?

The original series, no question. And my favourite character is one of the big three — Kirk, Spock, and McCoy. My choice changes daily. Outside of the main cast, I really like Richard Daystrom, Matt Decker, Vina, Gary Mitchell, Sarek, and Edith Keeler.

-

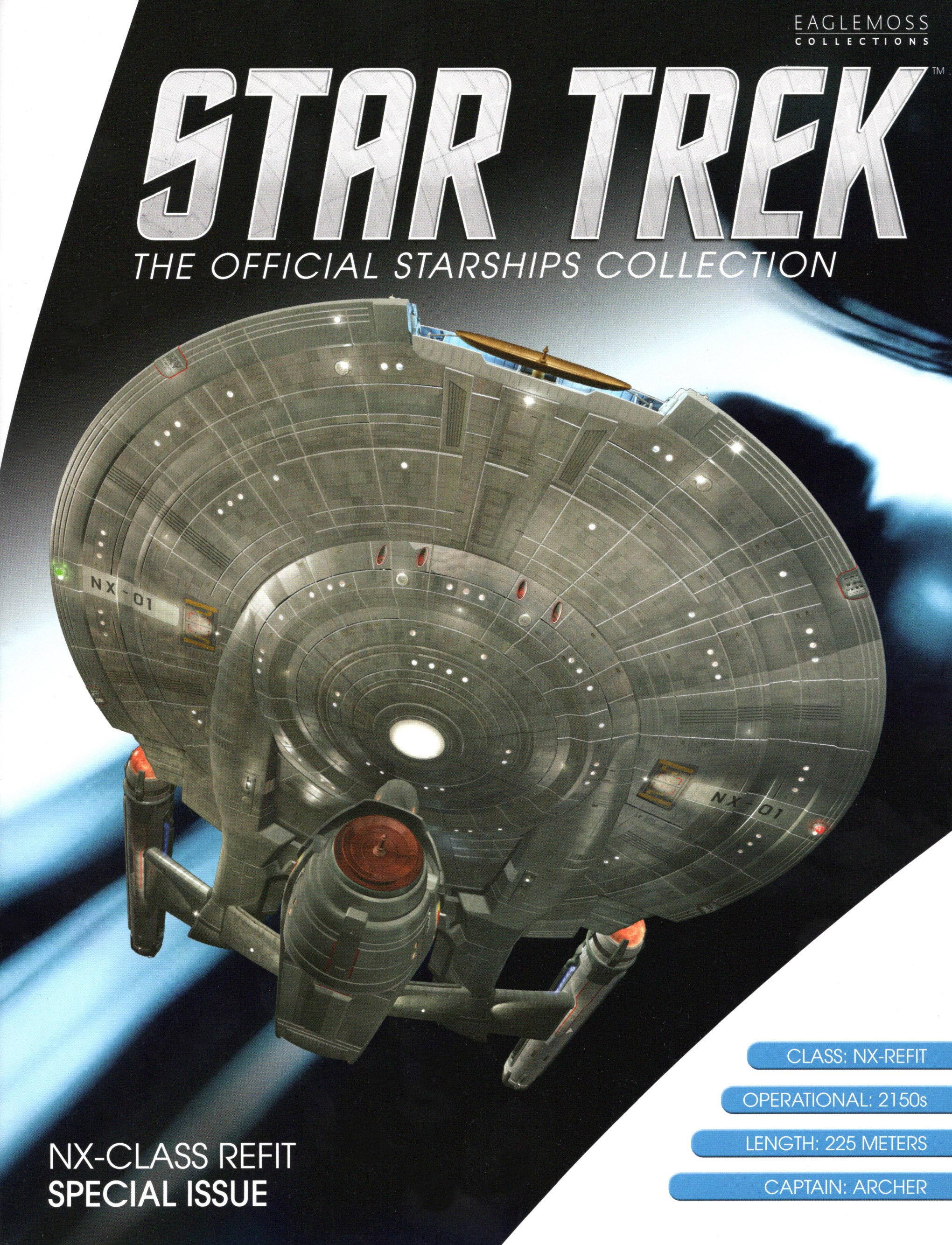

Doug Drexler on designing the NX-01

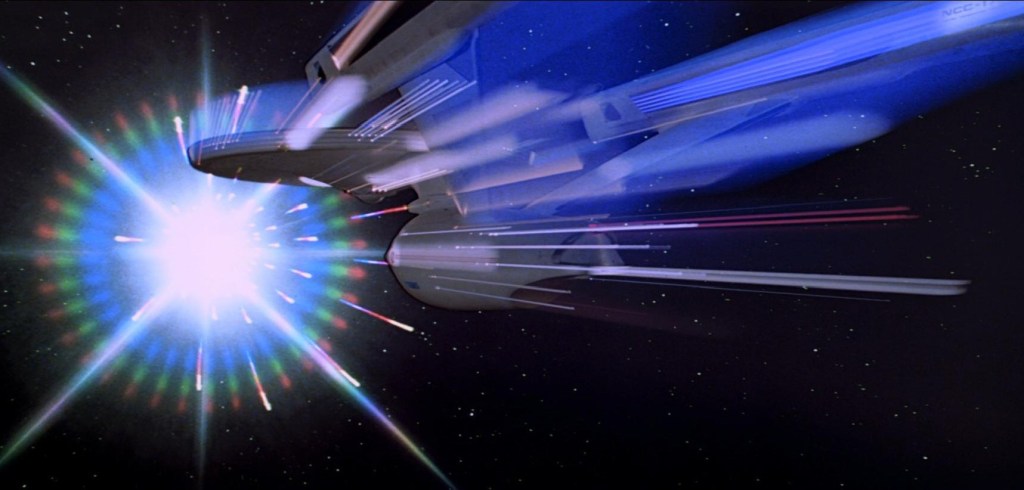

The greatest ship design in all of Star Trek is Matt Jefferies’ Enterprise. It’s both realistic and fantastical, and looks great from any angle. This is true from its first appearance in The Cage through to the unveiling of the refit Enterprise in that long, loving tribute at the beginning of The Motion Picture and into the debut of the 1701-A in Star Trek IV.

The hero NCC-1701 at the NASM and the NX-01 by Doug Drexler

The second greatest design is the NX-01, from Enterprise. It clearly predates Christopher Pike’s ship and it’s easy to see how it led to the NCC-1701 — especially if the secondary hull that designer Doug Drexler envisioned is added.

Enterprise was cancelled after four seasons but, had it gone further, one option for season five was the crew returning to Earth for an upgrade: the addition of a secondary hull. The warp-engine pylons which had connected directly behind the saucer would now extend down to the new section, with the saucer linked to the main hull with a small neck. This moved the NX-01 a big step closer to the ship that first appeared on televisions in 1966. And the fact we never got to see it on-screen is among the great disappointments that flow from the show’s cancellation.

Luckily for Star Trek fans, Eaglemoss gave us models of the NX-01 and the NX-01 Refit, so we can see what Drexler envisioned.

The Eaglemoss NX-01 and NX-01 Refit models Every detail sweated out

I was fortunate to speak with Drexler for a few stories on this site, and I also asked him about creating the NX-01. I had seen some statements online that the ship was designed very quickly, but Drexler told me this is not true. A number of ideas for the new ship from Production Illustrator John Eaves had not worked out, and the staff was approaching a deadline; Production Designer Herman Zimmerman and Eaves had to begin work on the interior of the ship. Scenic Art Supervisor Mike Okuda suggested Drexler be brought in. Drexler agreed to take it on, even though he already had a full-time gig elsewhere. And despite the deadline pressure, the eventual look was not rushed. Instead, he told me “Every detail of that was sweated out. More time was spent on the NX than on any other starship.”

Drexler also delivered a bonus: he had been learning about computer-generated imaging, a technology new to the Enterprise production offices.

I was at Foundation Imaging, learning to do CG. Art departments didn’t have CG yet…but I had spent two years at Foundation. So basically, Mike Okuda said to Herman Zimmerman ‘If you bring Doug back to the art department, he brings the computer knowledge with him, and we can model a ship and see it from any angle, with different light on it. But I had to give two week’s notice, I couldn’t just leave (Foundation Imaging) so Herman said ‘That’s okay, I’ll just come to your house at night and we’ll work on it.

I would come home from work and Herman would be sitting on my front porch. This went on for a couple of weeks.

But even as the design work progressed, the project was almost pulled out from under him. The higher-ups considered simply using an existing ship design.

At one point, Peter Lauritson, the Post-Production Supervisor, asked about a model of the Akira, and my heart sank. His idea was to just use the Akira. Herman and I talked about it and we decided we needed to push it more towards the [original-series] class of ship.

The pontoons that the engines are attached to (in my design) are similar to the P38 Lightning, a plane from World War II that I loved. That was my main inspiration. It made sense that, if we didn’t have a secondary hull, what is going to hold the engines on? Because you don’t want them near the primary hull. So we had twin booms like on the P38.

The Akira (left) from the old Drex Files site. The P38 is from The Aviation History Online Museum

Drexler finalized the basic design and then sold it with some CGI showmanship. “I did animations of it flying by the camera, and they had never seen that before.”

The secondary hull

Drexler is a TOS fan, and he had always looked up to Matt Jefferies. (“Matt Jefferies became extended family for me and the Okudas.”) He wanted his design to be a clear precursor to the NCC-1701, and that meant it too needed a primary hull.

I always planned that a second hull would be added. When I was building the approval model for the NX, I would always take that secondary hull and put it underneath, just to see how it worked. There was an evolutionary thread. They would go out for the first four years and have their asses handed to them and while that is happening, [Starfleet is] building a secondary hull for when the NX comes back. They would then refit it with that secondary hull.

An early test rendering of the Refit And, thankfully, Eaglemoss took that concept and produced a model of the NX-01 Refit, although sadly only in the company’s small size. I and a lot of other fans would have purchased an XL version.

Enterprise is not among the most popular of the Star Trek series, but even those who don’t love it should take a second look at the NX-01’s place in a starship lineage that eventually gave us TNG’s 1701-D and the 1701-E of First Contact. It fits perfectly, especially with the addition of the secondary hull, because Doug Drexler respected the artists who had created the design language of Federation starships. I wish the production team on Discovery had the same understanding of that aesthetic.

-

Read Harve Bennett’s first pitch for Star Trek III

Reading story treatments gives a glimpse into Star Treks that could have been, and it’s fitting to spend some time with Harve Bennett’s first version of what would become The Search for Spock as the 40th anniversary of that film just passed.

I am not going to summarize the pitch — hit the download link and enjoy the story in Bennett’s own words — but I will share some reflections on it.

Romulans would have been better. Bennett had Romulans as the big bads of the movie, and I think that was a better idea, for a couple reasons.

First is the casting of Christopher Lloyd as Kruge, which still divides fans. Lloyd threw himself into the role and there are bits of the performance I quite like, but seeing him on screen sometimes pulls me out of the movie. Oddly, that does not happen when watching him as Doc Brown.

But even putting aside the choice of actor, a badass Romulan on the movie screen would have been excellent. We had seen two Romulan commanders by that point, in Balance of Terror and The Enterprise Incident, and both were standout characters, full of charm and menace, and the movie could have given us a third antagonist on that level.

The Vulcan plot is a misfire. Bennett’s outline had an open revolt taking place on Vulcan as many demanded secession from the Federation in response to the “implications of universal Armageddon” represented by Genesis. Some fans like the political tension of this subplot, including Robert Myer Burnett. According to this Gizmodo article, Burnett felt the idea made this a more “serious, ‘perilous’ and above all epic story.” It’s possible Bennett’s eventual script would have added some great stuff about this threat to the Federation but in the outline this story goes nowhere; the Enterprise diverts to Vulcan and then a ship from that planet drops McCoy back on the Enterprise. You could cut those bits out and not affect the story at all.

More importantly, I don’t believe the existence of Genesis would prompt Vulcan to leave the Federation. Rather the opposite: the existential threat of enemies exploiting the technology makes it a logical imperative that the Federation remain united and resolute. I am glad this idea was dropped.

I also don’t like Saavik’s declaration of love. Look, Kirk is a sexy guy, but not every woman has to fall for him. Gillian Taylor’s rebuff is one of the best bits in The Voyage Home. In Star Trek II, there is no hint that Saavik is attracted to Kirk, so her admission here that “she has always loved Jim Kirk” is simply unnecessary.

So, a spy ship was equipped for large-scale mining? The Bird of Prey is described as “a spy ship, deep in enemy territory” but the discovery of dilithium transforms its crew into miners who, somehow, have all the equipment necessary for large-scale mineral extraction. That simply doesn’t make sense.

The idea that a ship could run a major mining operation worked in JJ Abrams’ 2009 film because the Narada had been a mining vessel. It could pull minerals off a planet. I don’t buy a spy ship doing the same.

Bennett nailed the big beats right off. The treatment delivered the two significant moments that would later appear in The Search for Spock: the team stealing the Enterprise after Scotty sabotaged the Excelsior and Kirk destroying his ship after tricking most of the enemy into boarding. Bennett knew how to deliver memorable scenes.

It’s great to see Sulu get so much to do. Sulu is one of the primary movers of the plot — and how often can we say that?

Ghost Spock and the “transcendental state” make less sense than the movie’s katra. Suspending disbelief is one thing; moviegoers had to stretch that muscle to accept the idea of a katra, the content of an entire life that could be copied through a mental link that lasted only as long as it takes to mutter “Remember.” Bennett’s outline asked people to go further, because he provides even less foundation for the survival of Spock’s personality and memories. Sarek says Spock may still exist in a “transcendental state” without explaining how that works.

And then people start seeing ghost Spock. First McCoy, then Kirk, and then the rest of the main crew encounter the first officer. Kirk even tries to talk to him.

It is suggested the sightings are real, and not simply wishful thinking brought about by grief. So, somehow the feral Spock who lives on Genesis is projecting his presence across space — or something. And that’s just silly. Again, Bennett may have fleshed out this idea but I can’t think of any way that ghost Spock would have worked.

But even with a few faults, Bennett’s outline is quite good. Many of the best beats in the finished movie are here, and I like his description of the Romulan commander as “a handsome, swarthy man with a dignity reminiscent of the 20th Century actor Omar Sharif… the Romulan is of blood and passion. His mission is intelligence.” I really wish we had met that character.

And Bennett even repurposed a good line from the previous movie, with Saavik telling Kirk “Self-expression has never been one of your problems…” It’s a nice touch.

-

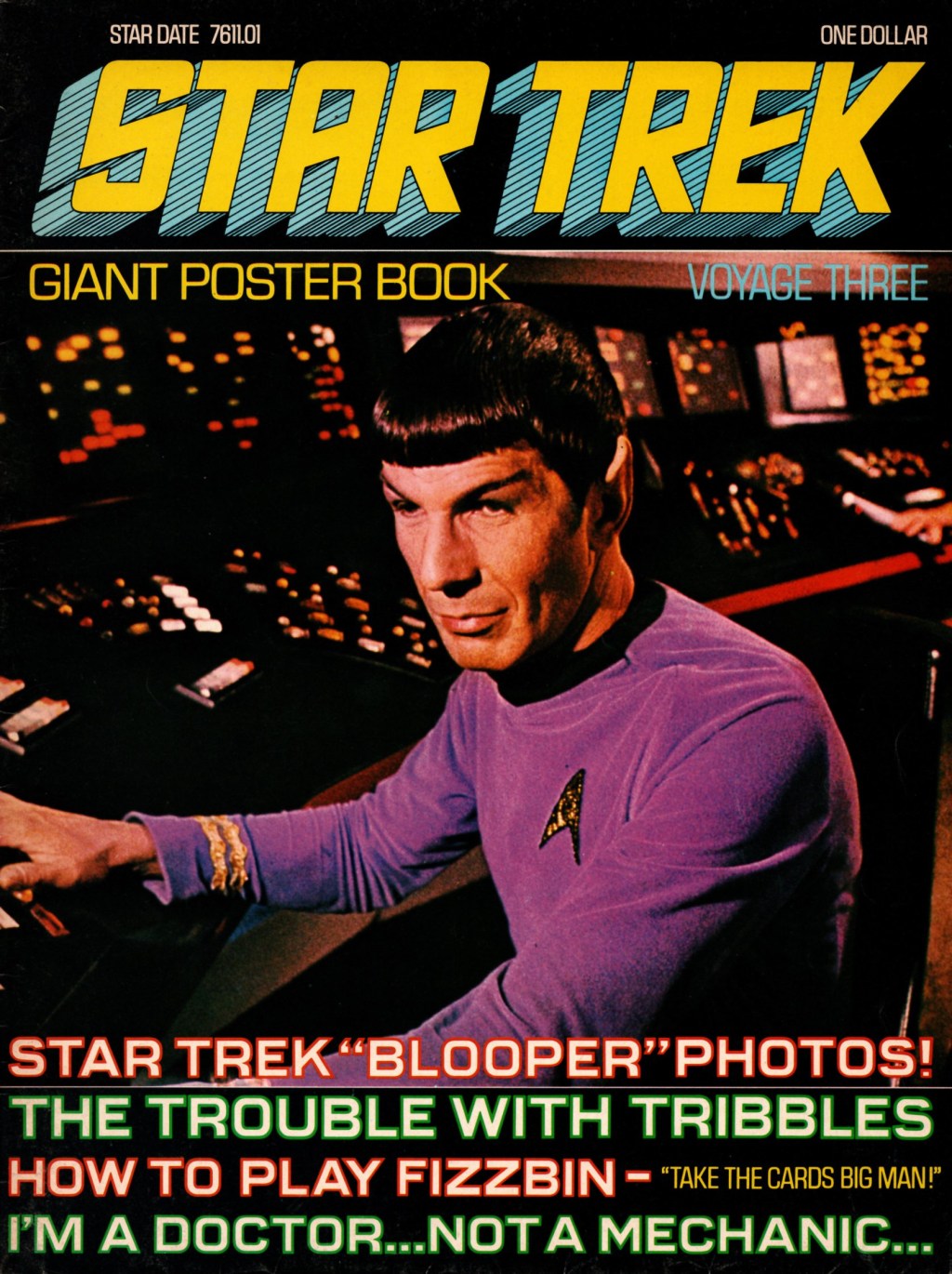

Giant Poster Book three: celebrating Trek’s funny side

The Star Trek Giant Poster Books were the first professionally published Trek magazines. Seventeen issues were produced between September 1976 and April 1978, plus a 1979 “Collectors Issue” devoted to The Motion Picture. Each delivered six pages of content plus the cover and back cover and folded out into a large poster.

I own the complete set and will cover each issue. The story of the magazine’s genesis is told here.

Here are highlights from issue three, published in November 1976, plus a scan of the magazine.

This issue was devoted to “the humor of Star Trek” and that was a good choice. The show did funny really well, even though Gene Roddenberry famously did not want his creation to concentrate on jocularity. That is understandable in the context of the 1960s: science fiction in general and Star Trek in particular were struggling to be taken seriously, and pop sci-fi often did not help.

David Gerrold, writing in 1973 in his The Trouble with Tribbles book, said that as early as 1966 he did not want Star Trek to “fall into the same trap of fantasy and pseudo-science fiction that had claimed—oh, say…Lost in Space. Lost in Space was a thoroughly offensive program. It probably did more to damage the reputation of science fiction as a serious literary movement than all the B-movies about giant insects ever made.”

But if Star Trek had to avoid becoming a full-on sitcom, it is also true that the funniest episodes — notably The Trouble with Tribbles and A Piece of the Action — are among the best loved. And this Poster Book focuses on both episodes, plus giving readers a set of screencaps from the blooper reels, in the days before you could just watch them online.

How to play fizzbin

Writer Anthony Fredrickson takes Captain Kirk’s line about fizzbin — “On Beta Antares Four, they play a real game.” — and builds a fanciful story about Saint Fizzbin and how the Antarians evolved the game to “earn the favor of the gods and win health, wealth, and longevity. Fizzbin is a way of settling debts, public and private. It is the basis of the Antarian court system [and] the most skillful Fizzbin players occupy Beta Antares highest government posts.” It’s a silly bit but suited to an article about an impossible game in an issue devoted to humour.

Fredrickson set out to write playable rules and did a good job of building some structure on Kirk’s improvisation, but you still can’t really play the game, and the text here is not quite perfect. In the episode, Kirk says that each player gets six cards, except for the player on the dealer’s right, who gets seven, but the magazine version has that as “except the dealer and the player to the dealer’s right, who get seven.”

Here is the dialogue from the episode, so you can compare the screened “rules” to Fredrickson’s version.

KIRK: Of course, the cards on Beta Antares Four are different, but not too different. The name of the game is called fizzbin.

KALO: Fizzbin?

KIRK: Fizzbin. It’s not too difficult. Each player gets six cards, except for the dealer, uh, the player on the dealer’s right, who gets seven.

KALO: On the right.

KIRK: Yes. The second card is turned up, except on Tuesdays.

KALO: On Tuesday.

KIRK: Oh, look what you got, two jacks. You got a half fizzbin already.

KALO: I need another jack.

KIRK: No, no. If you got another jack, why, you’d have a sralk.

KALO: A sralk?

KIRK: Yes. You’d be disqualified. No, what you need now is either a king and a deuce, except at night of course, when you’d need a queen and a four.

KALO: Except at night.

KIRK: Right. Oh, look at that. You’ve got another jack. How lucky you are! How wonderful for you. Now, if you didn’t get another jack, if you’d gotten a king, why then you’d get another card, except when it’s dark, when you’d have to give it back.

KALO: If it were dark on Tuesday.

KIRK: Yes, but what you’re after is a royal fizzbin, but the odds in getting a royal fizzbin are astro… Spock, what are the odds in getting a royal fizzbin?

SPOCK: I have never computed them, Captain.

KIRK: Well, they’re astronomical, believe me. Now, for the last card. We’ll call it a kronk. You got that?

KALO: What?

Watching the show as a kid, it always struck me that Kirk tells Kalo that a third jack would disqualify him but, when Kalo is dealt a third jack, Kirk says “How lucky you are! How wonderful for you.” What? I figured the captain was just making it up so it didn’t matter, but the script (at least the October 30, 1967 Final Draft) shows William Shatner flubbed the line. As written, Kalo was dealt a nine, and was told another nine would disqualify him. His next cards were two sixes, and Kirk says “That’s excellent.”

It appears Shatner improvised about half of his lines, but you can’t blame him, considering the script.

This is a fun article that by itself is worth the price of the magazine.

Critiquing Tribbles

Fredrickson opens his episode analysis with an interesting statement: “Don’t search for any ulterior motives deep in the meat of The Trouble with Tribbles next time you see it, it’s strictly a “fun” episode…” That opinion would surely have disappointed David Gerrold, who conceived the story as a commentary on invasive species. He told an interviewer in September 2016:

I thought, “We’re not going to recognize the danger with every alien we meet. The ones who are going to be the most dangerous are the ones we’re not going to realize are dangerous until it’s too late.” So I came up with the idea of these cute little fuzzy creatures. I was always fascinated by ecology, and I was inspired by the case of rabbits in Australia, this whole idea that they became predators because there weren’t any predators already there.

The last article is meant to be an examination of humour in Star Trek but it’s really just an “and then this happened” list of dialogue. If you’ve watched the show, you can skip this piece.

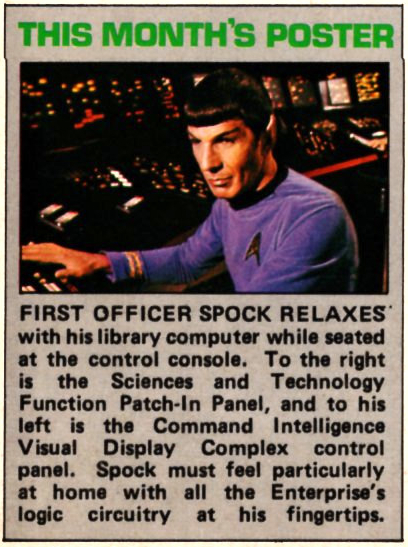

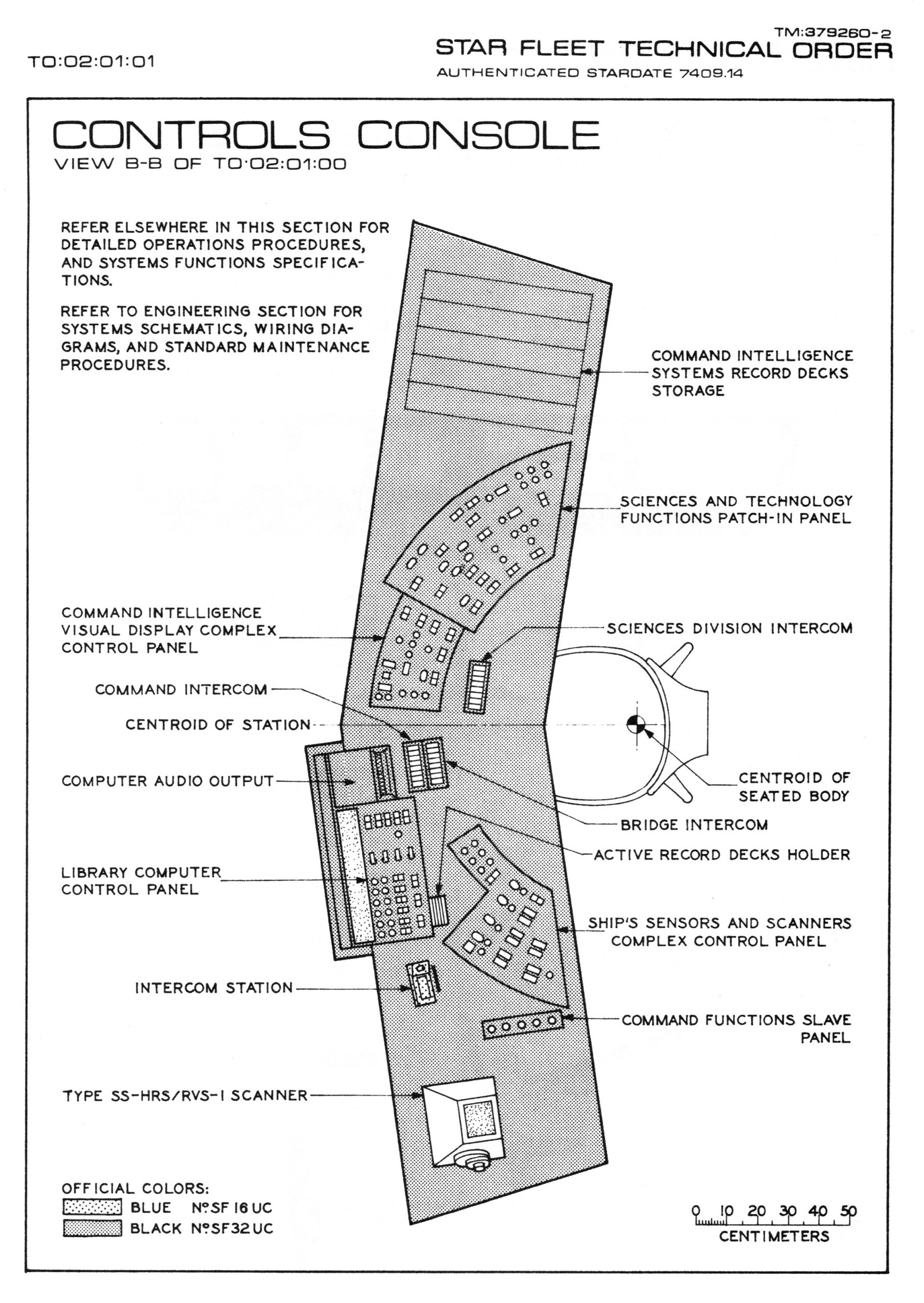

The issue closes with a pretty good trivia quiz, an ad for the Star Fleet Technical Manual and the Star Trek Blueprints ($6.95 and $5, including shipping!) and a description of Spock’s station on the bridge. Interestingly, the names assigned to the instruments are taken from the Technical Manual; they are never stated on screen.

-

Is the Enterprise bridge rotated 36 degrees?

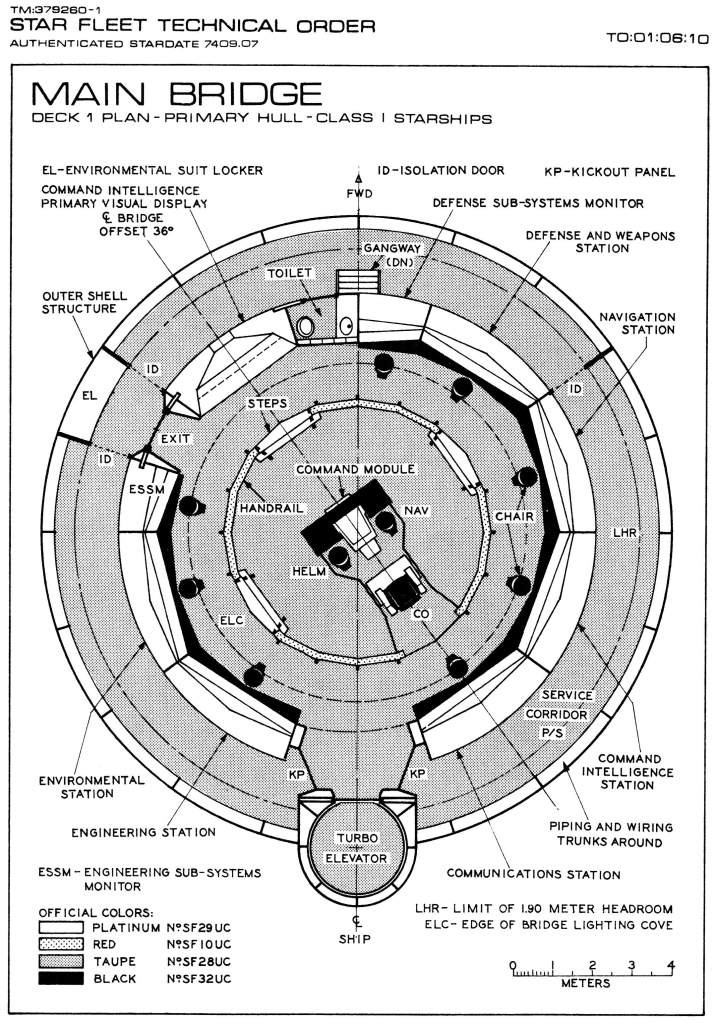

On-screen evidence can sometimes be tricky. Take the orientation of the bridge on the original-series Enterprise. The turbolift runs up the “neck” that connects the primary and secondary hulls, so the doors on the lift must be at the back of the bridge, relative to the centreline of the ship. That would locate them directly behind the command chair.

But that’s not what we see on screen. Instead, the doors are behind but over to the left of the command chair. This decision was made for camera angles and dramatic shots, but how do we square it with the “real world” of the Enterprise? There are two explanations.

Theory one: Joseph’s offset

Franz Joseph’s Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual, first printed in 1975 and beloved of a generation of trekkers, offers an elegant and mathematically sound solution: the bridge is rotated 36 degrees to port from the centreline. This accounts for the location of the lift relative to the command chair.

But that means the crew is not facing forward as the ship speeds towards Earth Outpost Four, or wherever. I had no problem with that when I got my first copy of the manual; I was just thrilled to have the diagram of the bridge and the rotation seemed a fine explanation. After all, the viewscreen is not a window that has to point forward. Also, the crew would not feel odd travelling at a 36-degree offset to their perceived direction as the ship must have technology that compensates for speed and direction changes. Otherwise, the jump to warp speed would liquify the crew. (This technology is the inertial dampeners but I believe that term was not used on-screen until The Next Generation.)

Theory two: the lift-car storage area

Some fans could not accept this explanation, so there is an alternative: a turbolift car arriving at the top of the shaft would jog to the left a little before the doors opened. We know the cars travel horizontally as well as vertically, and this little bit of lateral travel eliminates the need for the offset.

The theory also suggests there are multiple cars in the lift system, and there is a small “parking area” along the outer edge of the saucer, with cars waiting for passengers.

This explains how, in The Alternative Factor, Lazarus can exit the bridge and then a security guard can step into a different car a few seconds later.

Theory two is correct. Here’s the evidence

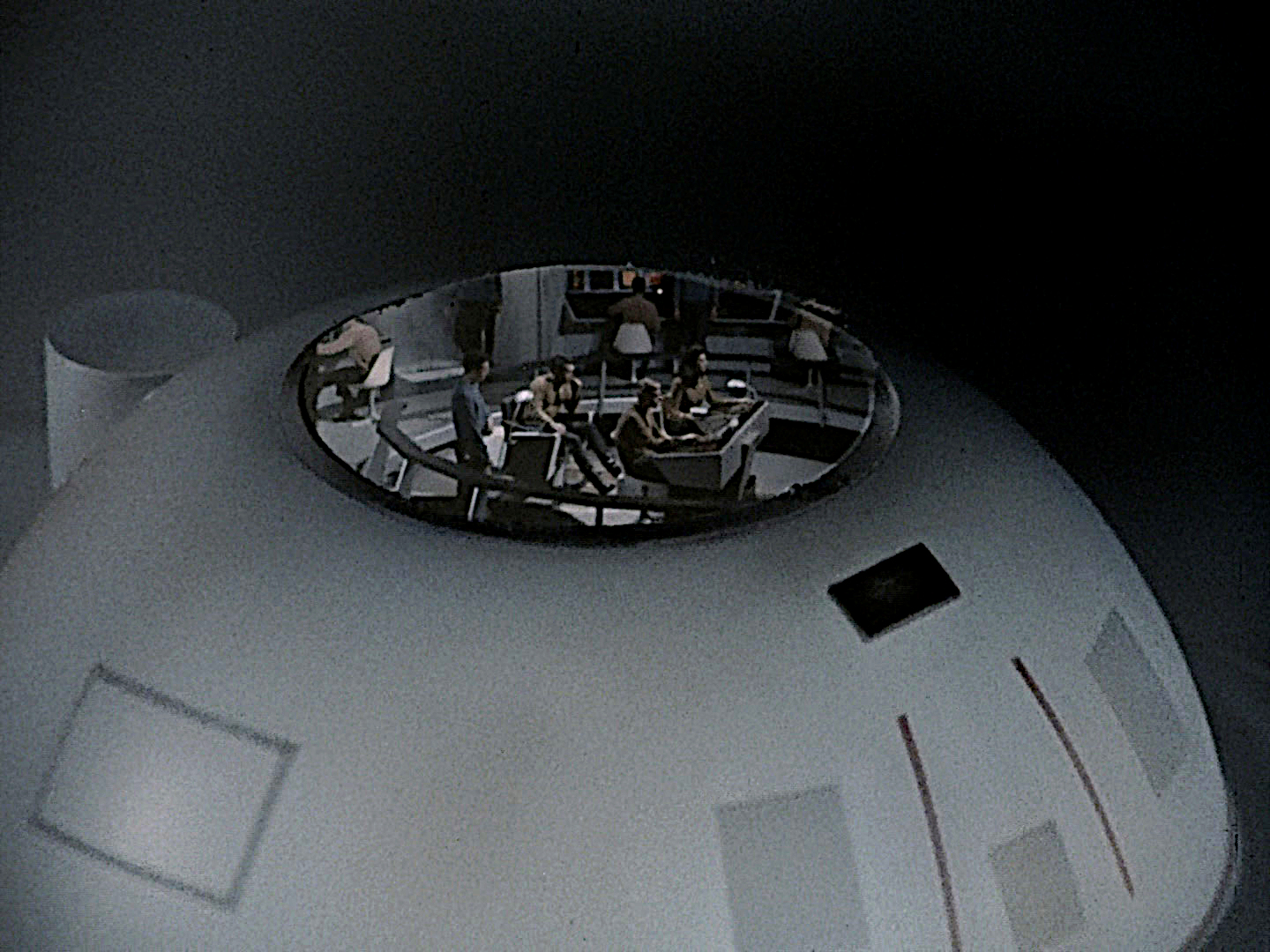

The Cage opens with proof that the lift cars take a quick sidestep just before the doors open on the bridge. This scene shows that the lift tube is located behind the command chair, while the doors are a number of degrees over. The cars must traverse that short distance.

I am afraid that Franz Joseph, brilliant though he was, got this detail wrong.

And there is one more piece of evidence. When the Enterprise encounters sudden resistance, the crew is thrown directly forward — as if the bridge is oriented along the ship’s centreline. For example, in The Immunity Syndrome the crew lurches towards the viewscreen as the ship first enters the body. Scotty staggers in from the right going in a different direction and then everyone starts flying all over the place (especially that poor guy tipping over the railing near the end) but it’s fair to say that the intent of the scene is that the bridge is oriented in line with the ship’s forward motion.

The remastered version of this episode does a good job of explaining this by showing the Enterprise being buffeted in different directions as soon as it penetrates the boundary, but I am an original effects guy.

This forward motion is more clearly visible in The Wrath of Khan, but as some people pointed out (notably Mark Farinas, @trekcomic on

TwitterX) that bridge could have been reconfigured during the refit. (It’s fun to note that all the crew lurch forward except for Kirk. It looks like Shatner wanted his character to appear especially unmovable in this moment.)The Cage and The Immunity Syndrome present the best evidence that the bridge is not rotated off the centreline. And that confirms Kirk is looking directly towards where his ship will go during his “Out there. Thataway” gesture at the end of The Motion Picture.

-

Stephen Hawking said warp drive is possible — but scientists aren’t working on it

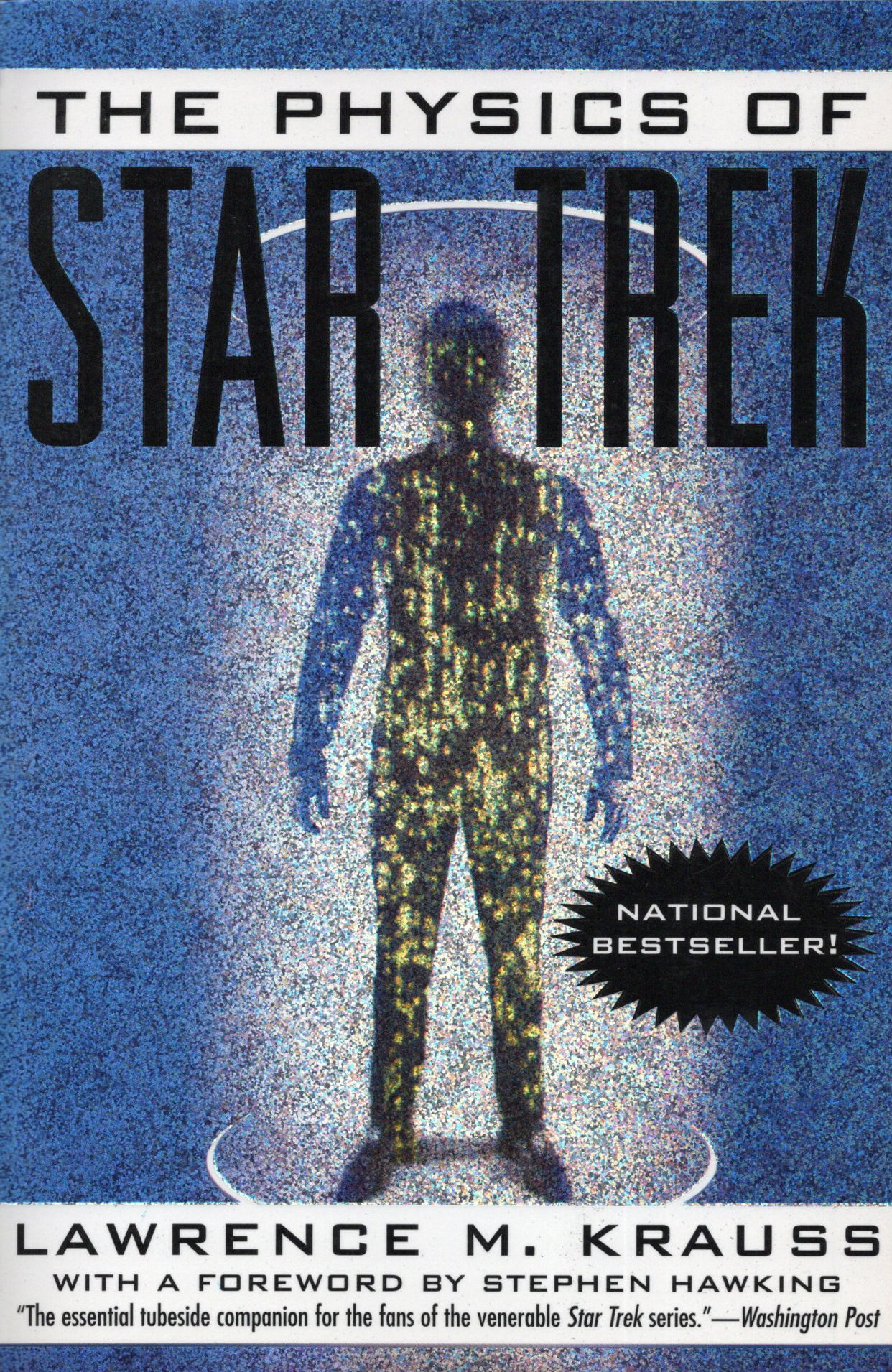

I own about 160 Star Trek books but I must admit I have not read them all. One in that category is The Physics of Star Trek by professor Lawrence M. Krauss. I pulled it out of a storage box recently and spotted Stephen Hawking’s name on the cover. The famous physicist wrote the foreword — and that was worth checking out.

Before we get to what Hawking wrote, I should say that I kept reading after his bit and was drawn into the book. Krauss knows his Trek: the book opens with an imagined scene aboard the USS Defiant just before the interphase begins in The Tholian Web. I was impressed, and the book is very approachable and full of Trek content.

Back to Hawking. The foreword is brief but he does make an interesting statement about warp drive.

One thing that Star Trek and other science fiction have focused attention on is travel faster than light. Indeed, it is absolutely essential to Star Trek’s story line. If the Enterprise were restricted to flying just under the speed of light, it might seem to the crew that the round trip to the center of the galaxy took only a few years, but 80,000 years would have elapsed on Earth before the spaceship’s return. So much for going back to see your family!

Fortunately, Einstein’s general theory of relativity allows the possibility for a way around this difficulty: one might be able to warp spacetime and create a shortcut between the places one wanted to visit. Although there are problems of negative energy, it seems that such warping might be within our capabilities in the future. There has not been much scientific research along these lines, however, partly, I think, because it sounds too much like science fiction… The physics that underlies Star Trek is surely worth investigating. To confine our attention to terrestrial matters would be to limit the human spirit.

My Starfleet-wannabe heart beat a little faster as I read that because, as Hawking said, faster-than-light propulsion is required for the adventures we see on screen — and for the adventures we all dream of living. We don’t want to set course and arrive in a couple of years. We want to set course, play a little 3D chess, lunch on a chicken sandwich and coffee, spend the evening at a Christmas party in the science lab, and wake up just before we drop out of warp near a strange new world.

It’s nice to think that only some scientific effort stands between us and the Phoenix, but Hawking also wrote that public priorities often get in the way: “Imagine the outcry about the waste of taxpayers’ money if it were known the National Science Foundation were supporting research on time travel.”

Sci-fi author and professor Adam Roberts also sees this problem, and he blames futuristic TV and movies for making real space travel seem dull. Roberts wrote in the book Boarding the Enterprise that:

It is the very success and popularity of science fiction itself that finished off the Space Race… SF is too good at what it does. Why should people bother with real space flight when fictional space flight is so much better in every way — more exciting, more engaging, more satisfying (and with a better view)? The idea of traveling to the stars is something that touches the souls of most human beings, but why should they invest emotionally and intellectually — and therefore financially — in actual space technology when they can get so much more from fictionalized space flight?

It’s a valid point but I hope Hawking’s opinion that it is worth investigating these possibilities eventually takes hold, and that “some kind of star trek” will inspire scientists. We’ll know in about four decades.

Collecting Trek

A TOS collection 40 years in the making