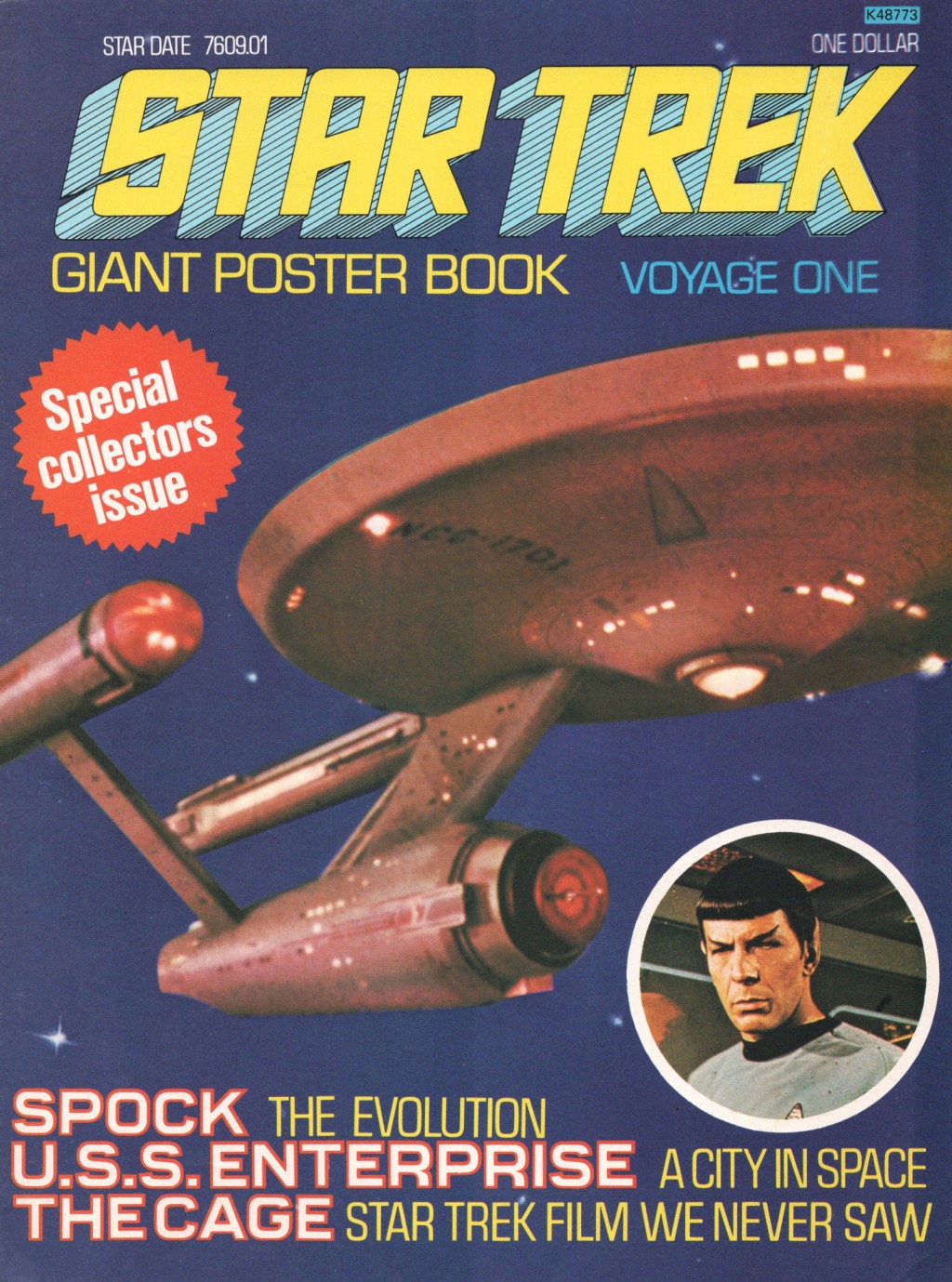

The Star Trek Giant Poster Books were the first professionally published Trek magazines. Seventeen issues were produced, printed almost every month from September 1976 to April 1978, plus a 1979 “Collectors Issue” devoted to The Motion Picture. Each magazine delivered six pages of content plus the cover and back cover, and each folded out into a large poster.

I own the complete set and will cover each issue. The story of the magazine’s genesis is told here.

Here are highlights from issue one, published in September 1976, plus a scan of the magazine.

There are many reasons to like the Star Trek Giant Poster Books. The biggest, for me, is that they were a thinking-person’s take on Star Trek. Issue one has none of the standard, expected articles, like a list of best and worst episodes or a “What is William Shatner doing now?” piece. Instead, readers were given a profile of the Enterprise as a living character, an analysis of Spock as a modern hero, and — best of all — a study of the first-draft script of The Cage. This is especially interesting because, as Allan Asherman and Doug Drexler wrote in 1976, “only a few copies remain” of this first draft. Today, they must be even rarer. I have a copy of the second draft but I have never seen the first.

The quality and insights delivered here are remarkable. Also, each issue gave readers a big freaking Star Trek poster! How great is that?

The editorial

The editor’s greeting is unsigned but was presumably penned by Ron Barlow, who wrote that he struggled to come up with a message for this first issue. I’ve known that challenge myself, but despite his concerns Barlow says one really important thing: this magazine will “let readers know you’re at home.”

And that is what the production team delivered. The entire run is a warm welcome to fans who love Star Trek from people who treat it with affection and knowledge.

The U.S.S. Enterprise: A city in space

The first article explains how the show’s sound design places the viewer in a busy and purposeful city setting. The writer, Drexler, tells readers that the bridge set is practical, functional, and visually appealing but that:

It is the imaginative use of sound that adds the final touch, that brings the complex to life. The constant chirping of relays and computers remind us that hundreds of functions are being monitored and controlled at all times.

Reports are constantly filtering into the bridge from onboard stations. We become more and more aware of the tremendous network of people on board through the imaginative use of sound alone. Even if we were never to see another crewmember we would be aware of their existence, we hear them and they are active.

The Cage: Scenes unproduced

The Cage opens on the impressive bridge of the Enterprise and with a crew that is on edge, dealing with a red alert and a mysterious distress signal. Viewers are dropped into a tense situation already in progress.

That’s the filmed version. The first draft of the script opened instead on a more routine activity: the Enterprise is exchanging passengers with a shuttle and the captain, Robert April, is grousing that his new yeoman is too young.

Some personnel are also being transferred off April’s ship, and Roddenberry had this captain too deal with recent deaths among his crew, although the scene is a little more raw than what we later got from the series. One crewmember confronts April:

Crowley: You send me back this way, April, they’ll disqualify me as a navigator, break me as a ship’s officer.

April (interrupting): You fired on friendly aliens, cost us four dead, three injured…

Crowley (interrupts angrily): They looked like insects. How could I know that they were intelligent enough to have weapons?

April (quietly): Get off my ship, mister.

Roddenberry also wrote a lengthy description of warp drive, which we see in The Cage as the transparent starfield overlay and Jose Tyler’s seven-finger communication to Pike.

The whine of electric circuits and the high pitched signals of computers rise enormously in volume as Mr. Spock engages a control. A strange shifting-color radiance seems to emanate from the inner walls of the vessel. Spock engages the master control. Suddenly every sound is abruptly stilled. Then even more startlingly, the scene seems to dim and begins to become transparent (EFFECT: double exposure)… The transparent shadow of Captain Robert April moves to the astrogation position, eyes the navigator’s work. The figure of Jose turns, holds up seven fingers; April nods toward Mr. Spock who acknowledges, disengages the master control.

As the article authors rightly point out, the “complicated warp scene would have necessitated the same multiple exposures every time the ship wanted to get someplace fast, which would not only have cost more money but would have detracted from the drama present during such occasions.”

The first poster book cost $1 in 1976. This article alone is worth the buck.

Spock: An analysis

Asherman makes a number of interesting observations about Spock but what really stands out in this piece is how much these guys knew about Star Trek, in the days before Memory Alpha and the reference books that today crowd my shelves. The article tells us that Spock’s home world was originally called Vulcanis, that Nimoy’s arched eyebrows and pointed ears were airbrushed to look more normal in an early promotional booklet, and that The Corbomite Maneuver was filmed in June 1966. Accessing that information is trivial today, but how did Asherman know all that in 1976?

The poster

The Enterprise is slowly entwined in The Tholian Web.

Errata

No one is perfect and there are a couple of errors in the issue. Asherman’s statement in his Spock article that “Gene was also the head writer of Have Gun Will Travel” is often repeated but untrue — although to be fair Roddenberry himself regularly spread that story. The other (really small) error is Asherman’s statement that Leonard Nimoy was in Rocket Man, made by Republic Pictures. Nimoy actually appeared in Zombies of the Stratosphere, which used footage from Rocket Man.

Click here to read about how these magazines came to be.

One response to “Giant Poster Book One: a magazine that told readers “you’re at home””

[…] Collectingtrek.ca has added a new review for Allan Asherman and Doug Drexler and george snow‘s “Star Trek Giant Poster Book: Voyage One”: […]

LikeLike