There are about 140 original-series reference and non-fiction books worth owning. One stands out for sheer oddness: the Star Fleet Medical Reference Manual.

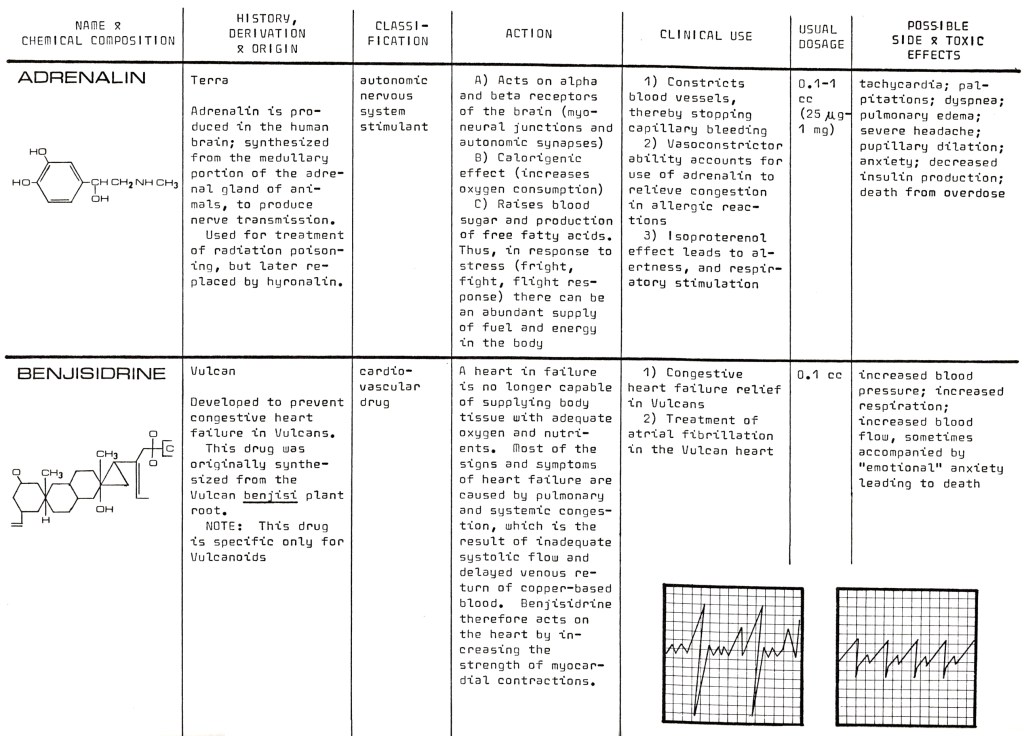

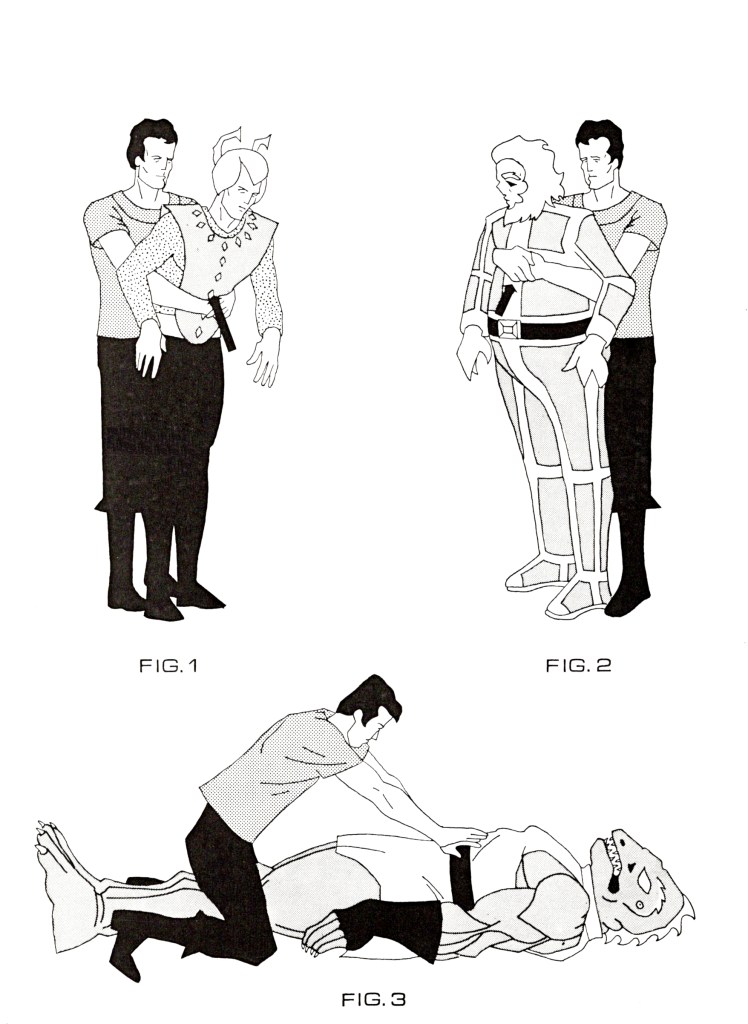

About half of this delightful 1970s fandom jetsam is like a real-world textbook, with lists of diseases and drugs, instructions on lifting injured persons, and information on the Heimlich Maneuver, CPR, and resuscitation. The other half is fanciful speculation on the species — humanoids, non-humanoids, parasites, and plants — that filled Star Trek, plus information on otherworldly elements, psionic studies, and the requirement that “each Starship shall have in its health crew complement at least one person so designated as a Doctor of Chiropractic.” A chart will inform you, quite correctly, that palladium is represented by the symbol Pd, has the atomic number 46, and was first identified in England in 1803, and then the next entry is about pergium, Pe and atomic number 111, which was discovered on Mercury in 2023.

The book is a decidedly odd mix of fact and fancy and one of its creators, Star Trek luminary Doug Drexler, told me that most of the people who worked on it didn’t really want to.

“It’s a strange anomaly of a book that we would not have done except that Ron had this girlfriend,” he said, referring to Ron Barlow, with whom Drexler worked at the storied Federation Trading Post, a Star Trek store in New York City in the 1970s. “Ron had a girlfriend, Eileen Palestine, who was a registered nurse and she had the idea of doing the Medical Reference Manual. I thought we could have spent the time doing something more interesting.”

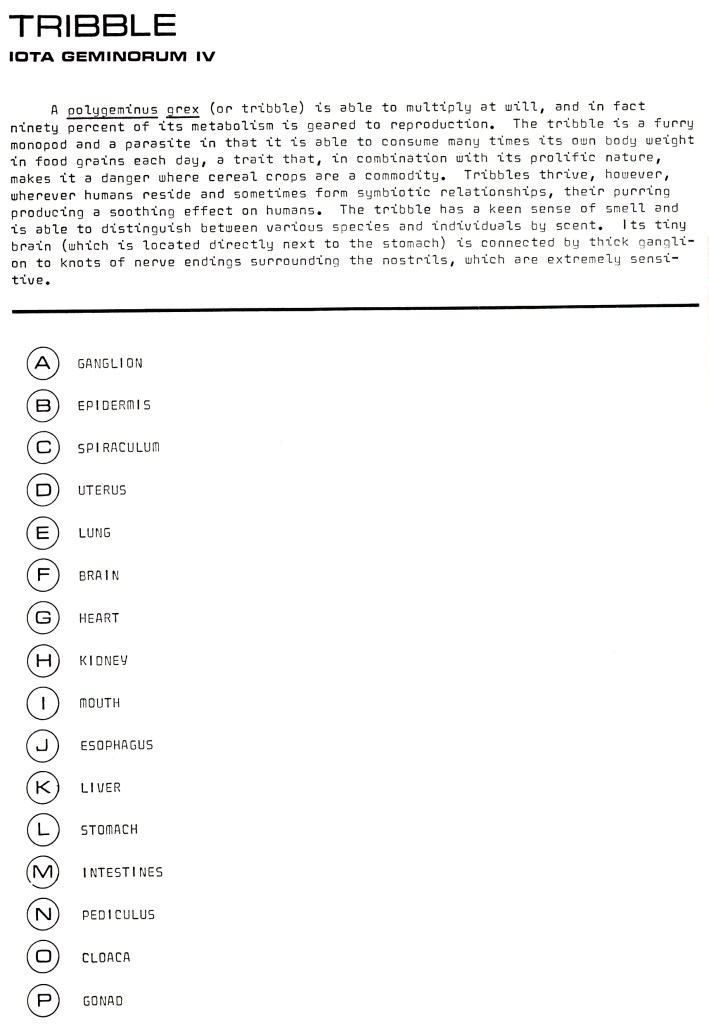

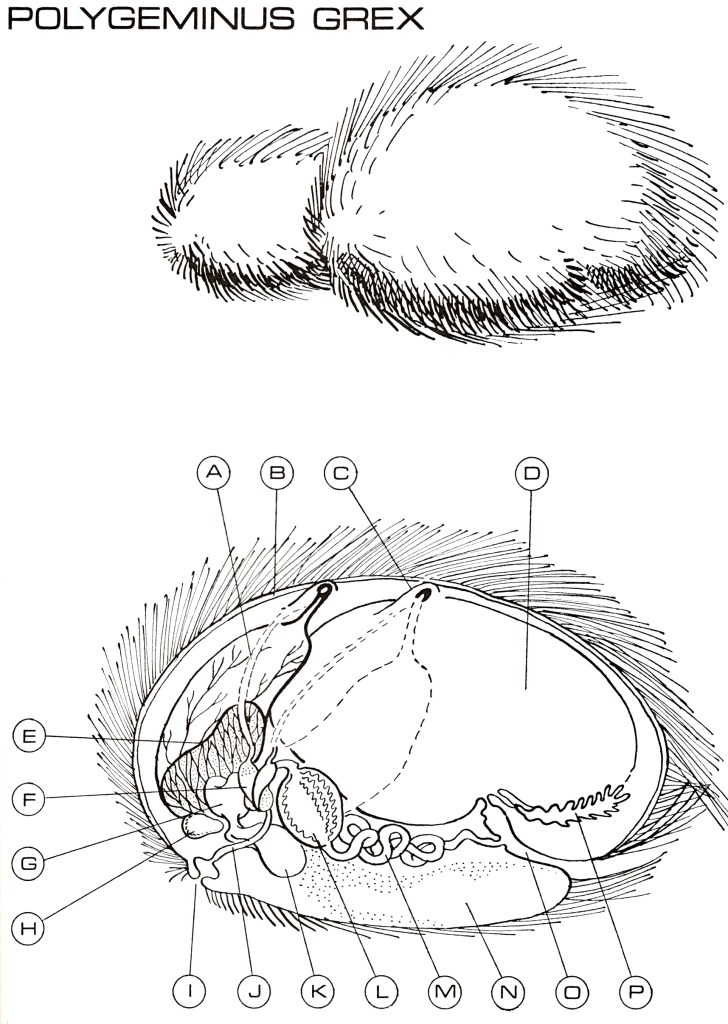

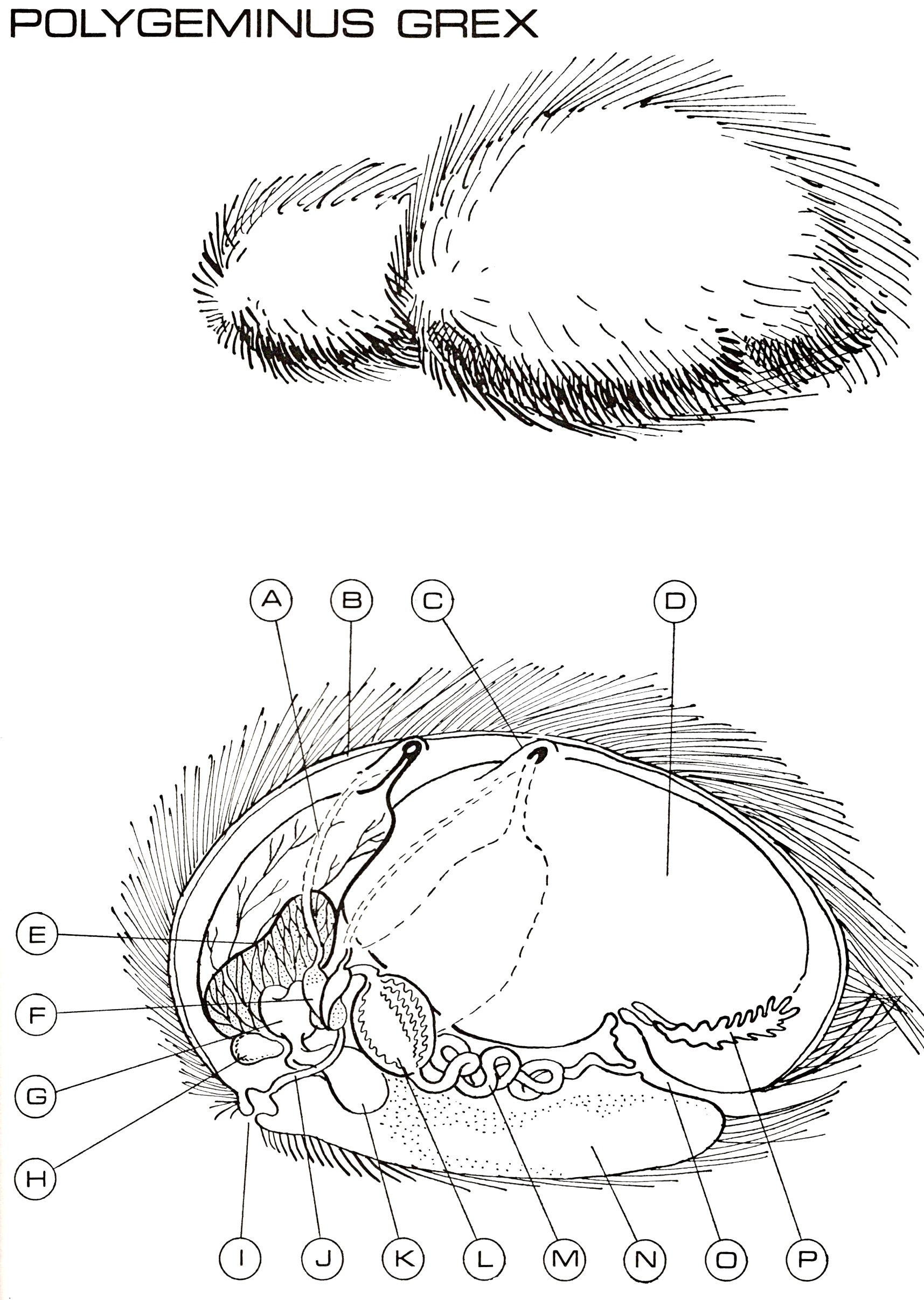

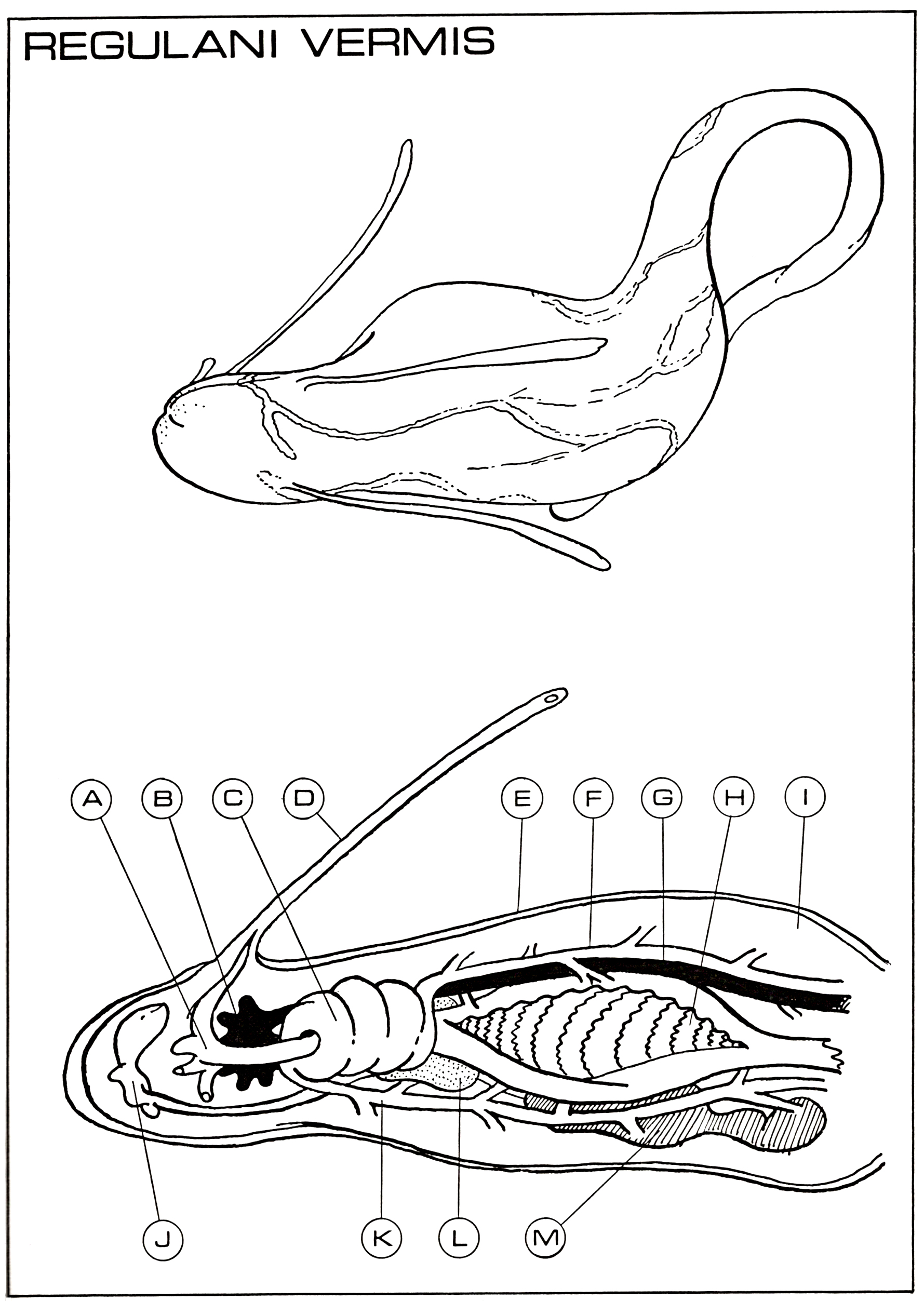

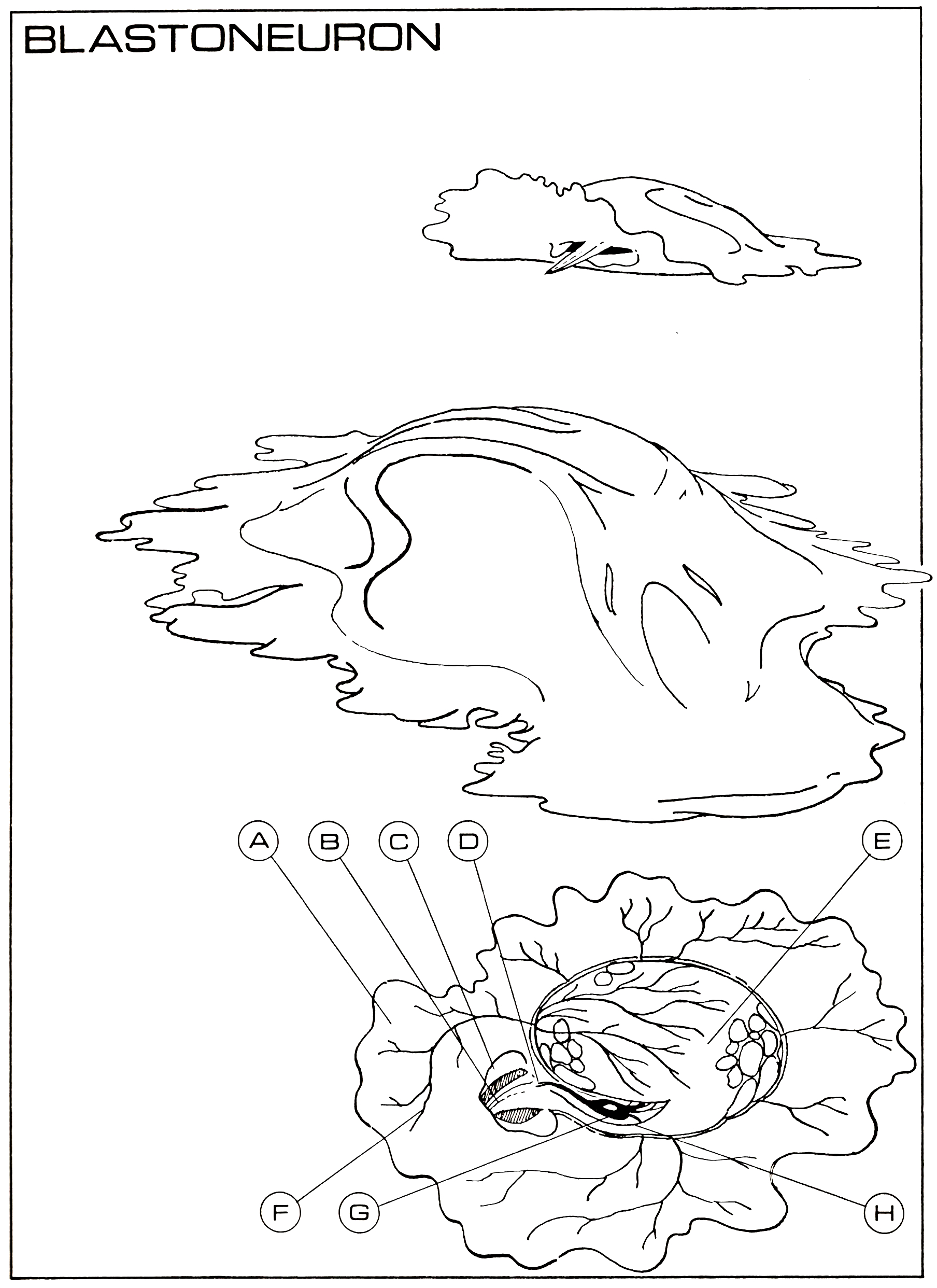

Barlow and Palestine convinced Drexler, store employees Geoffrey Mandel, Mitch Green, and Anthony Frederickson, and others to work on the book. The team was tasked, for example, with describing the Tribble digestive system and then Frederickson had to draw it. “We had to say to ourselves ‘How are we going to figure this out?’ but we did it for Ron’s girlfriend. We would rather have been doing ships.”

Palestine handled the medical information and she and Barlow wrote the text, while the rest worked up the illustrations. Drexler cannot recall which of them drew each one. The first version of the book, a fan edition with a shiny white cover, was sold in the store.

Then one day “a guy came into the Federation Trading Post and he had a contract with Ballantine Books to do a Star Trek book, and he knew nothing about Star Trek. He came in to pick our brains.”

The publisher sent the man’s manuscript to the store for a review — and it was terrible. “We told Ballantine that, and they cancelled the book with this guy,” Drexler said. “We had the fan edition of the Medical Reference and they saw that and said ‘Well, we could make a book out of this, if you want.’ And that’s how it happened.”

The book must have been at least fairly successful, as its first printing in October 1977 was followed one month later by a second.

The happenstance nature of its publication is typical of 1970s Star Trek merchandise, much of which was created by semi-professional fans who started out making unlicensed items for themselves or for sale at conventions.

Then DS9 made a bunch of it canon

Drexler worked as a scenic artist on Deep Space Nine, and when the producers needed some graphics for the wall of Keiko O’Brien’s classroom in season one, they grabbed illustrations those store employees had created more than a decade earlier.

Seven drawings were colourized and used on a display labelled Comparative Xenobiology, seen here in the episodes A Man Alone and The Nagus.

Which makes the location of Horta ovaries canon.

One response to “Revisiting the quirkiest Star Trek book, with Doug Drexler”

[…] Collectingtrek.ca has added a new review for Eileen Palestine‘s “Star Trek: Star Fleet Medical Reference Manual”: […]

LikeLike