A personal note: Howard Weinstein is a really nice guy. He spent a lot of time corresponding with me and even pulled together detailed notes, shared personal anecdotes, dug through his files, and sent me scans of documents. From one Star Trek fan to another, thank you, Howard.

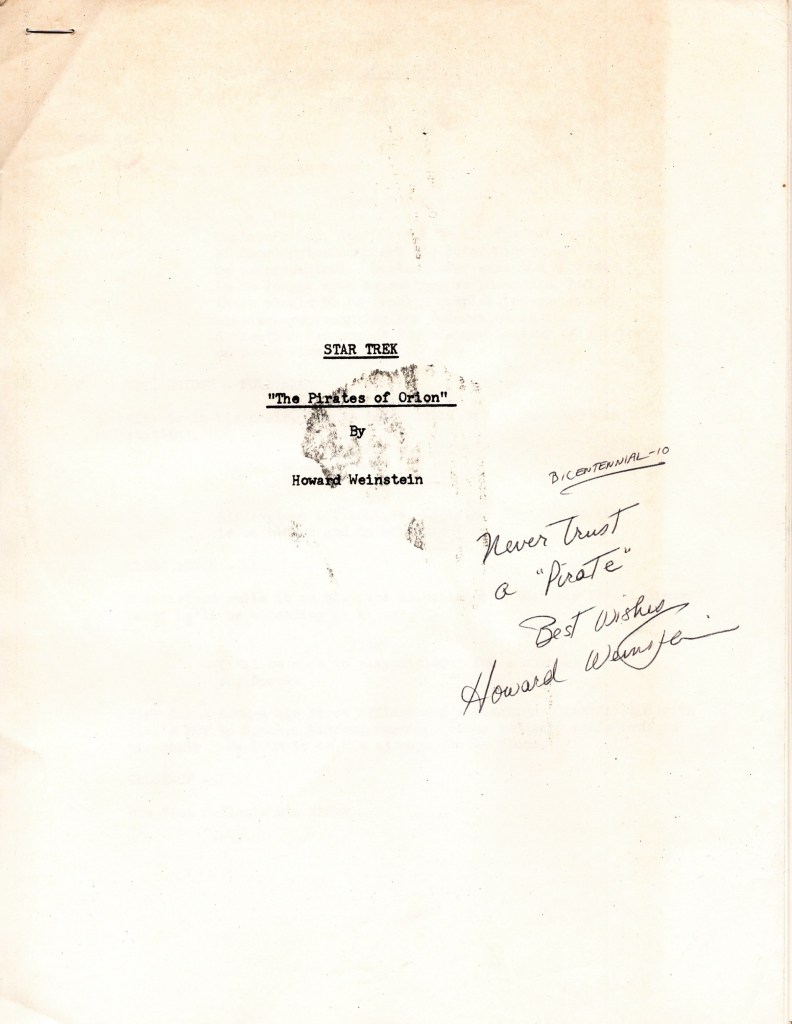

Sometimes you get really lucky on eBay. A seller in Alberta recently put a big lot of Star Trek paper up for auction, mostly old fanzines, but the description was vague and it drew no interest. But I spotted one critical photo in the auction’s jumble: the cover page of a script with Howard Weinstein’s autograph.

I knew of his work, of course. Weinstein sold The Pirates of Orion to Filmation at the age of 19, and it became the first episode of season two of The Animated Series. Weinstein then built an impressive career: he is a New York Times bestselling author and has produced 17 books, including novels (seven of them Star Trek tales), non-fiction, and graphic novels, plus 65 Star Trek comics.

This is the story of how Weinstein became a very young professional writer, of the kindness of DC Fontana, and of what Filmation co-founder Lou Scheimer taught him about writing for animation.

First, the eBay script

I have been collecting for a long time, and I have shelves, walls, and boxes full of Star Trek memorabilia. Recently, my focus has narrowed to the 15 years that stretch from the making of The Cage to the premiere of The Motion Picture.

The eBay auction promised: “Star Trek Memorabilia, 76/77 Year Books, Issues Of News Letters All In Pictures! Condition is Very Good.” The seller did not mention the Pirates script, and I won the lot for the ridiculous price of $0.99. Some of the other stuff is good but the gem is clearly the signed script.

My goal with Collecting Trek is to tell the stories behind my collectibles, so I launched into research mode. The wonderful Fanlore site informed me that “The Bi-Centenntial-10 Star Trek convention was held at the Statler Hilton on September 3-6, 1976. Approximately 5,000 fans attended.” The also wonderful Trekker Scrapbook offered up program scans that confirmed Weinstein was indeed at the convention, participating in a series of “Animation techniques” panels.

My next stop was a StarTrek.com interview with Weinstein and then on to the contact page of his web site. I sent him a brief email:

I recently acquired a script for your The Pirates of Orion episode. It is on old paper, stapled in the corner, and typed on both sides. The cover has been signed by you: Bicentennial-10. Never trust a “Pirate.” Best Wishes, Howard Weinstein.

That would be the 1976 convention in New York. I have a Star Trek collectibles site and I am working on an article on the script, and I am writing to ask if you can tell me anything about it. Were these copies that you sold at conventions? Please let me know, if you can.

Weinstein replied promptly. And thus began a lengthy correspondence.

Not a real script

I own a few outlines and scripts that came from the actual typewriters of the authors (including Ted Sturgeon’s Amok Time outline) but this is clearly not that. Although it is on old paper, it is not the original that Weinstein typed out in his college dorm room. Nor is it an actual Filmation script. For one thing, it has text on both sides of the paper; real scripts are printed on one side only. Weinstein told me:

I remember those Pirates script copies being sold, but I wasn’t the one selling them. One of the dealers got hold of a script and then photocopied and sold them for a while. I have a vague recollection that the dealer asked me to sign a bunch of them, which I did.

Which means that Weinstein agreed to sign pirated copies of his own work. As I said, he’s a nice guy.

Episode specifics

Weinstein then answered a bunch of my queries about the episode itself.

Extrapolated stardate. The Pirates of Orion is essentially a sequel to Journey to Babel. In Pirates, Spock is struck down by the illness choriocytosis, which is deadly to Vulcans. Kirk arranges to rendezvous with the freighter SS Huron to receive a shipment of the antidote but it is hijacked by pirates from the planet Orion and Kirk has to outwit the other captain to retrieve the medication.

As Weinstein said to me: “Pirates was definitely inspired by Journey — what other mischief might the Orions be up to?” He continued:

My main inspiration was the Kirk/Spock/McCoy friendship; by putting Spock in lethal jeopardy via the rare disease I cooked up (choriocytosis), I got to explore Kirk and McCoy’s shared determination to save their friend. I’m happy to say I still think it’s a pretty decent little story.

Indeed, and Weinstein drew a clear connection to Journey to Babel by having Kirk reference the episode, saying at one point: “Orion’s neutrality has been in dispute ever since the affair regarding the Coridan planets and the Babel Conference of stardate 3850.3.”

3850.3. Including that number jumped out at me, because it is not really required. So I checked. In Babel, Kirk states three stardates: 3842.3, 3842.4 and 3843.4, and the reference to 3850.3 was too close to be a coincidence. I asked Weinstein “Did you actually use the Journey to Babel dates as a starting point?” and the answer is impressive for those days before the Internet, DVDs and Netflix.

I had Kirk refer to the actual Babel conference, not the Enterprise voyage that delivered the ambassadors to the conference. So I guesstimated a stardate for the conference itself.

The SS Huron. The script has the USS Potemkin (a nice callback to The Ultimate Computer) handing the medication off to the SS Huron — not the USS Huron. I asked: Was not going with “USS” intentional, as it was a freighter instead of a starship? And indeed it was: “I’m guessing my thinking was that the Huron would’ve been a merchant ship, not a Starfleet ship.”

Filmation, however, depicted the ship on screen as the USS Huron, even though Kirk states “SS” in dialogue, but the studio did add one nice detail: its serial number is NCC-F1913, with the F indicating freighter.

The pirates of OR-ee-on. I knew this must be a perennial question but I could not ignore the odd way every character says the word “Orion.” I asked: “Orion is pronounced on screen as “OR-ee-on” and by multiple actors recording in different locations, which means someone decided on that pronunciation. Do you have any insight into why that pronunciation was used?

Yes, I got asked about that a LOT in the old days. Here’s what some of the actors told me: For the first few episodes of TAS, they got together at Filmation and recorded the dialog like a radio play. After a while, that became harder to arrange, so Filmation would send the actors their scripts and they’d tape their own lines at home, or wherever they happened to be. In order to make sure the cast all pronounced certain words the same way, they were given a phonetic guide to certain words, like planet and alien names. For some reason lost in the mists of time, someone at Filmation decided the well-known word Orion would not be pronounced the way the rest of the universe says it — Or-EYE-an — but would be spoken as OR-ee-on. And nobody ever caught or corrected that before the scripts were sent to the cast.

It’s impossible to watch the episode without the pronunciation really standing out, but this was also the show that had pink tribbles and purple uniforms on the Klingons.

The story of the sale

“As a 19-year-old rookie writer, it was all pretty exciting,” Weinstein says of selling the script to Filmation. Here is that story.

The Pirates of Orion was originally a short story I’d written at age 16, for East Meadow, NY, high school’s annual one-shot science/sci-fi magazine in 1971, when I was co-editor with my friend Mark Greenstein.

I also did something I’d often do later when I wrote 65 Star Trek comic books for DC, Marvel, Malibu, and WildStorm – I dug up a tidbit from past Star Trek continuity and explored it in more depth. In the case of Pirates, it was the Orions. Other than Vina in her guise as a green Orion slave girl in The Cage and The Menagerie, what little we knew about them came from off-screen participation of Orion pirates in the excellent episode Journey to Babel (by D.C. Fontana).

After watching the first few animated episodes in the fall of 1973 (my junior year at the University of Connecticut), I was very eager to try submitting a script (as yet unwritten). So, in October ’73, I wrote a letter to Dorothy Fontana, known to Star Trek fans as D.C. Fontana, writer of some of the best TOS scripts. She was listed as script consultant on the animated series, so I asked about the proper time and procedure for sending in a script for season 2.

The fact that Dorothy replied within two weeks shows her kindness, courtesy and professionalism. Her letter told me several important facts: 1) they only accepted scripts through agents; 2) they’d bought none of their first 16 stories from outside writers; 3) they’d only be buying 6-8 additional scripts for season 2; 4) they expected word from NBC about renewal in early 1974; and 5) Dorothy herself wouldn’t be working on the show after season 1.

Dorothy’s letter made it clear that my quest to sell a script to the animated series had a very small window of opportunity, and the odds were very much against me. Thank goodness 19-year-olds are boldly clueless enough to think the rules don’t apply to them, and that merit and gumption count. We’re really idiots at that age, but idiocy can have its virtues in certain limited circumstances – such as believing I could do the near-impossible.

Luckily, Weinstein had an agent. His father’s childhood friend Bill Cooper was a Writers Guild of America agent and took Weinstein on as a favour to an old chum.

Here is Fontana’s letter. It chronicles her decision to distance herself from Star Trek, a separation that would last for many years, and it is a piece of history that I greatly covet.

Weinstein had purchased an I, Mudd script from Lincoln Enterprises to learn how to write for TV, and typed out Pirates over the Christmas holiday break.

Following the info in Dorothy’s letter to me, Cooper sent my script to Filmation in January ’74 – but addressed to “D.C. Fontana” – who by then had left the show. Filmation then forwarded the envelope (unopened) to Dorothy, who mailed it back to Cooper (still unopened, and unread).

So the script traveled coast to coast and back again – without anybody reading it. Talk about frustrating!

And here is the considerate letter Fontana sent when she returned the script.

Weinstein resubmitted the script to Filmation co-founder Norm Prescott once the renewal for season two was announced. He was in the shower at his dorm when his mother called with good news.

So I wrap myself in a towel and pad drippingly back to our room, pick up the phone, and my mother yells: “You sold your script!!” Filmation co-honcho Lou Scheimer had called my agent, my agent (not having my college phone number) called my parents, told my mother the news, and she called me.

A telegram and a cheque followed.

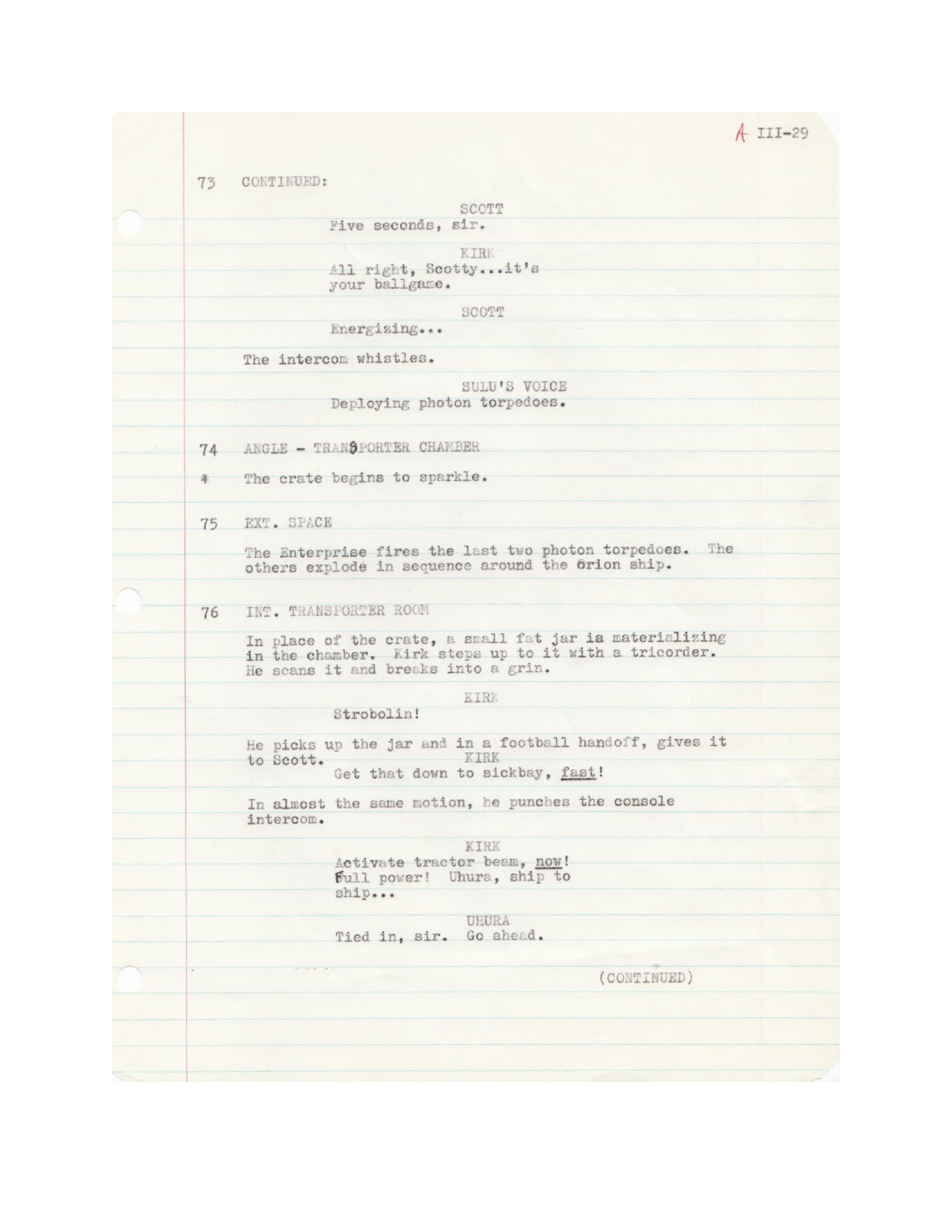

The network had ordered six episodes for season two of the series, and Filmation had only five months to get them ready. The studio didn’t ask for many changes to the Pirates script but one was important:

The main thing Lou Scheimer wanted me to do was get them off the ship.

Digging through my files, I see I wrote three alternate endings within a couple of weeks. As in the high school short story, the first draft script had the climactic confrontation between Captain Kirk and the Orion pirate captain taking place mostly on the Enterprise bridge and viewscreen. I’d initially been influenced by the live-action show, where getting them off the ship was expensive – requiring new sets or location shooting. Lou taught me a valuable lesson I had to relearn 20 years later when I wrote Star Trek comics: when anything a writer can imagine can simply be drawn by artists, you’re freed from live-action budget restraints. A planet surface, alien city, or interior of an exotic alien ship costs the same as drawing the bridge of the Enterprise.

Lou challenged me to be more visually creative, so I wrote a couple of new endings with Kirk and the Orion captain (voiced by Jimmy Doohan) duking it out on the colorful surface of an asteroid. We settled on the climax that was most streamlined and least talky.

Here is the original ship-bound ending, before the rewrite.

That original version then closes with the same last few seconds that we saw on screen.

The watch party

The story of that sale ends in a university dorm room, with a group of friends and a second date with a cute young woman.

I didn’t know until mid-August that Pirates would be the first show of the new season, airing September 7, 1974. That would be at the end of my first week back at school – and a week before my 20th birthday. I immediately passed the news along to as many friends as I could, and when I got back to UConn I told college buddies and invited them over to my dorm room to watch on my little 11-inch black and white TV. Somehow, we crammed 30 kids and one dog into the room – sort of a Star Trek mini-con.

A couple of friends had brought along a bottle of sparkling wine and plastic champagne glasses, so when the show started and my name appeared, everyone raised plastic glasses in a toast.

I’d also met a cute freshman that first week at the local pizza joint, and when we went out on our first date the Friday night before Pirates would be on, I shyly asked if she’d like to come over the next morning to watch my TV episode. Although she wasn’t a big Star Trek fan, and didn’t know anybody else, she did join the party. We’re still friends all these years later, and she still remembers.

Selling that episode launched Weinstein on a lifelong career as a writer, culminating in a long string of professional sales and more than one appearance on the New York Times bestseller list. (See his web site for details.) It also helped him sell his first Star Trek novel — The Covenant of the Crown — and prompted Leonard Nimoy to consult with him on the development of Star Trek IV. But that is a story for another blog post.

To this day, he is proud that he impressed Star Trek’s creator.

While I didn’t have any interactions with Gene Roddenberry, Lou told me that Gene had read and liked the script, and said it was one of the better first-draft Star Trek scripts he’d seen. Naturally, that praise made me feel pretty good.

Thank you again, Howard, for your time and generosity.

4 responses to “How a high-school story and a DC Fontana letter launched Howard Weinstein’s writing career”

This is such a great story – and well told as always. I love that Howard has shared so much of the background and context with you and I’m sure you’ll continue to exchange stories for years.

LikeLike

I hope so. He’s a fascinating guy.

Thanks for reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, I’m curious: Do you have other items in your collection – books, comics – that he wrote?

LikeLike

Of course! I have all his TOS comics, many if not all of his Trek magazine articles, and most of his TOS novels. (I stopped buying the novels in 1994, although I may pick that up again.) The publication scans at the end of the piece are items from my collection.

LikeLiked by 1 person